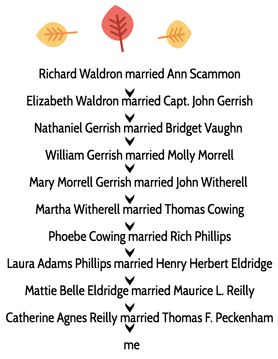

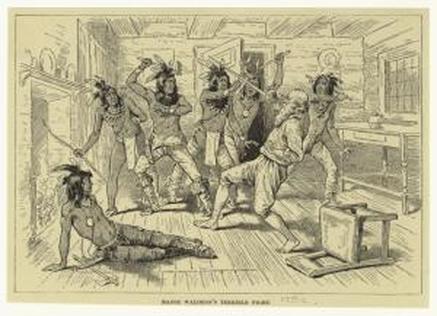

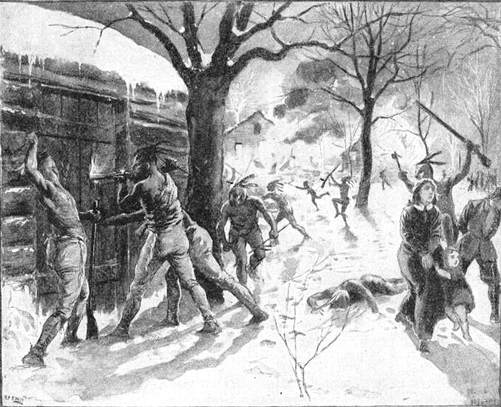

I had hundreds of people in my family tree already, enough to keep me busy tracking down ancestral profiles for years to come. I did not need to find Richard Waldron in my bloodline, but when I did, all the angst of responsibility for the actions of my ancestors flooded back. Must my life create a thousand acts of contrition to erase the legacy of such a man? Richard Waldron came from the group of Puritans who put their family fortunes to profit in the Massachusetts colony. He came first to Boston in 1635 and for two years surveyed and purchased land. He returned to England, married, and returned to settle in Cocheco, now Dover, New Hampshire, where he built a sawmill and a gristmill on the river, along with a trading post, where Native American traders suspected him of cheating them. Within 15 years of settling in Dover, Waldron had three children and his prominence in the Massachusetts Bay Colony kept rising. Elected to the General Court of Boston in 1654, he served for nearly 25 years, some as speaker of the house. Punishing the Quakers Waldron also earned a reputation for harshness when, in 1662, he ordered constables in eleven towns from Dover to Boston to tie three Quaker women to a cart and whip their bare backs publically. In the depth of winter, through snow, the women were marched to Hampton where they were whipped. In Salisbury, the local constable, Sgt. Major Robert Pike, balked at Waldron’s order then sent a team to intervene and bring the women to safety on the other side of the Piscataqua River. The poet John Greenleaf Whittier portrayed the Quaker persecution, depicting how the Quaker women might have cursed him: "And thou, O Richard Waldron, for whom In 1672 Waldron was commissioned a military captain, then major-general in the province of New Hampshire. He led the failed campaign against the French and Indian raids on English settlers on the coast of Maine and in Acadia in 1676 and had frequent dealings with the local Pennacook Indians, who remained neutral during the King Phillip War. Yet, with hostilities all around them, the people of Dover lived in homes that were barricaded like garrisons. After the King Phillip war ended, dozens of the warriors who fought the British took refuge with the Pennacook Indians. Waldron was ordered to seize all the outside warriors but he had instead proposed inviting the men to a military game event in Dover where he tricked them out their weapons. Once captive, the wanted men were separated from the Pennacooks and taken prisoner., two hundred men in all. Eight of them were executed and the rest sold into slavery, an offense that the Pennacooks would not forget. Thirteen years later, the Pennacooks, now under a new leader, took their revenge. In an well-planned move in June of 1689, they sent Penacook women to ask for overnight shelter at the five garrisoned houses in town. It was a rainy night and all but one of the women were allowed in. After midnight, the women slipped the bolts and opened the door to the revengeful Pennacooks. The slow torture and death of Richard Waldron is not one for the weak of heart. Reports say he tried to defend his household with his sword but was quickly overcome. His head was split open and his bleeding body tied to a chair in the main room. Pennacook men took their time with him, each cutting an X into his chest to signify their trade accounts with him were closed. Still alive, his ears and nose were chopped off and stuffed in his mouth. When he had little life left, his tormentors rigged his sword so he would fall on it and deliver the final death blow. Other members of his family were killed and his house burned to the ground. His six-year-old granddaughter, Sarah Gerrish, was taken prisoner. Waldron’s daughter Elizabeth Gerrish was safely at home with her husband and her other children, including nine-year-old Nathaniel Gerrish, my direct ancestor. In all, 23 people were killed and 29 captured that day in Dover. Waldron’s son and grandsons rose to great prominence in the state of New Hampshire and are now part of the legacy of the Granite State.

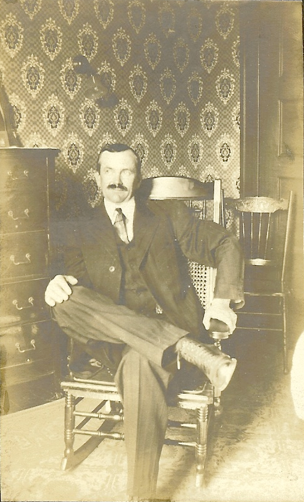

Richard Waldron's grandson, also named Richard, was a prominent political leader of colonial New Hampshire in the 1730s and 40s. He is not directly related to me. Here's his portrait

5 Comments

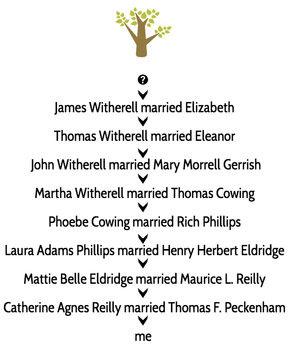

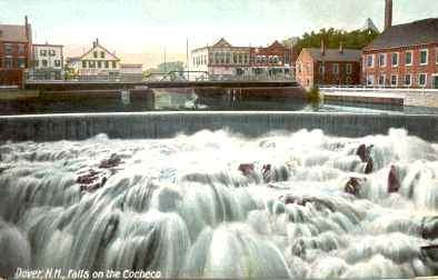

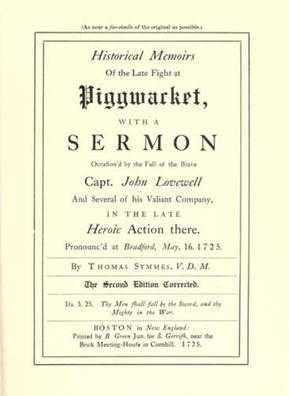

I had been poking around the Witherell branch of our family tree for days, hoping to unearth some clue that would link my ancestor James Witherell back to the Witherell family in Scituate, Massachusetts. James Witherell first appears in the public record in 1723, with no record of who his parents were. If he had descended from the Mayflower passenger Stephen Hopkins whose great-granddaughter married a Witherell in 1696, then my ancestral line would be tied to an important historical figure. I could not find any reliable record of who James' parents were but as I combed through the details I found that James had served on a military expedition to Lake Winnipesauke in 1723. That expedition, it turns out, was part of one of most violent periods of colonial history, marked by violent attacks by French priests and local Abenaki Indians on the English settlers, who fought back aggressively from their heavily fortified homes near the Maine coast and along the Merrimack River. Indian raids of settlers came in waves beginning in the 1690s on settlements from York, Maine to Dover, New Hampshire and Haverhill, Massachusetts, You can find many bone-chilling stories of men, women and children murdered or kidnapped, then forced to walk to Canada where they were sold by their captors in French Quebec. James Witherell appeared in Dover, New Hampshire in 1723, when tensions in the region were high. He would have been 18 that year, old enough to volunteer with the militia being formed by noted Indian hunter, Captain John Lovewell. Lovewell, of Dunstable, New Hampshire, had lived all his life in a garrison under threat of attack. As a youth, he developed expert hunting and tracking skills and used them to fight the Native Americans who threatened their settlement. Once the Massachusetts General Assembly offered to one hundred pounds for each Indian scalp, the promise financial gain led to more aggressive attacks. Lovewell and a few men attacked and killed seven Native Americans as they slept by their campfire. Several months later, in September 1724, two men who worked in his saw mill were kidnapped in a raid by French officers and Caughnawaga Indians and a posse of eleven men went after them. Ambushed at the Merrimack River, ten of the militia lost their lives. "Of worthy Captain Lovewell, I propose now to sing, Lovewell petitioned the Massachusetts General Court to allow him to assemble a militia to go after the raiders who had killed so many of his men. The court agreed to pay each man two shillings and six pence, along with the one hundred pound bounty per scalp. James Witherell would have been one of 30 men handpicked by Lovegood to join the first expedition to Lake Winnipesaukee in December 1724. Lovegood recruited fighters from throughout Massachusetts, with volunteers from towns north and west of Boston, from Groton, Lancaster, Billerica and Haverhill, as well as some men from Dunstable. James Witherell, whom history has not yet connected to his parentage, could have hailed from any of these towns. The men trekked north on snowshoes over deep snow from Dunstable to Lake Winnipesaukee, then another forty miles northwest. With supplies dwindling, they came across two Native Americans sleeping, killed the man and scalped him, then took a boy captive, to be sold as a slave. With money for the scalp and slave, Lovewell embarked a month later on a second mission to Lake Winnipesauke, this time with 87 men. Thirty men had to be sent home once provisions were depleted and, after three weeks of hunting, the militia encountered an encampment where Lovewell led them in a nighttime attack. An early account says the strike was preemptive as the Native Americans had marched from Canada carrying new weapons supplied by the French to launch an attack on the English settlers. In the incursion, Lovewell and his men took 10 scalps that they stretched on hoops and mounted on poles, marching triumphantly through Dover, New Hampshire and on to Boston, where they received one thousand pounds. James Witherell’s name does not appear in any of the accounts of this raid, or a battle two months later in Pigwacket, when Lovewell lost his life. James Witherell apparently settled in Dover, where he married by 1729. He was granted common land in 1733 and practiced the trade of cordswainer, making boots, and later sold seven acres of land in the Concheco Falls to a leather tanner he likely knew. In 1740 he was served again in a training militia, the 2nd Foot Company of Dover. He had three children and his grandson, John, ended up in Lebanon, Maine, from where he served in American Revolution as a sergeant in Captain John Goodwin’s Co., under the command of Major David Littlefield, in the disastrous Penobscot Expedition. John’s daughter, Martha, married Thomas Cowing, and the two of them moved to Dedham, Maine, where their eternal graves now sit on this hill. Martha’s mother, Mary Morrill Gerrish, has her own interesting line to pursue, taking us back to Dover, New Hampshire in the late 1600s. Stay tuned. References

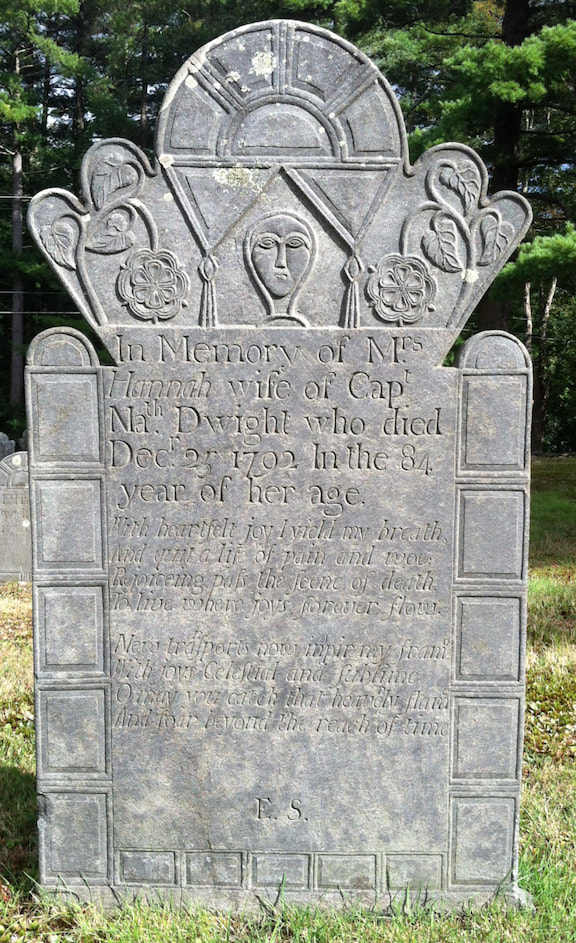

The original account of Capt. John Lovewell's "great fight" with the Indians at Pequawket, May 8, 1725 by Symmes, Thomas, 1678-1725; Bouton, Nathaniel, 1799-1878. The Scalp Hunters: Abenaki Ambush at Lovewell Pond, 1725, by Alfred E. Kayworth and Raymond G. Potvin. History of Nashua, New Hampshire, Part II, from the First Settlement to 1702. Notable Events in the History of Dover, New Hampshire: From the First Settlers in 1623 to 1865, by George Wadleigh. Colonial Wars of North America, 1512-1763 (Routledge Revivals): An EncyclopediaBy Alan Gallay History and genealogy of the Witherell/Wetherell/Witherill family of New England : some descendants of Rev. William Witherell (ca. 1600-1684) of Scituate, Plymouth Colony, and William Witherell (ca. 1627-1691) of Taunton, Plymouth Colony by Witherell, Peter Charles, 1943-; Witherell, Edwin Ralph, 1943- joint author History of Middlesex County, Massachusetts: With Biographical Sketches of Many of Its Pioneers and Prominent Men, Volume 1 A gravestone carver in the family tree? Who knew! I discovered the legacy of Joseph Sikes while researching my Marshfield ancestors in Springfield, Massachusetts. Joseph Sikes and his son Elijah not only carved headstones in Massachusetts and Maine in the late 18th century but their work is now celebrated as colonial art. Joseph is also my 4th great-grandfather, the grandfather of Sarah Sikes who around 1840 married John Hickey, an Irish immigrant to Maine. (You can read more about the Hickeys here.) He also managed to serve in the Revolutionary War from December 15, 1776 until March 18, 1777, marching 220 miles to take part in the battle of Princeton. He served again for two days in June 1782, in nearby Northampton to “suppress a mob.” Curious about these headstones, I began seeking them out in Chesterfield and Belchertown, Massachusetts and in Scarborough, Walpole and Pemaquid, Maine. Joseph Sikes was born in Belchertown, Ma. in 1743. It is believed he learned to carve from other members of the Sikes family in Connecticut. But his work is distinct and his images haunting. He often carved schist, which unfortunately does not stand up well to the ravages of time. Sikes almost always featured the face of the deceased on the headstone, encircled with ivy vines, rosettes, hearts, stars or moons. Occasionally he would include a winged cherub, a popular symbol at the time. Benjamin Ludden's stone in Chesterfield, Ma. shows Sikes' classic features of ivy and a spoon-shaped face. After arriving in Maine around 1790 his style evolved more. Some of the faces he carved had hair that surround the face like a lion’s mane. Other stones show men and women with shoulder hair that flipped up at the neck. Virtually all of the faces feature closed eyes that are carved as half circles. Elijah Sikes' headstones in Massachusetts are perhaps the most creative of all. Despite his prolific career creating memorial headstones throughout New England, the whereabouts of Joseph Sikes gravesite remains a mystery. He was reported to have died in 1802. His last known residence was Bristol, Maine. If you have any clues to where he is buried, please contact us!

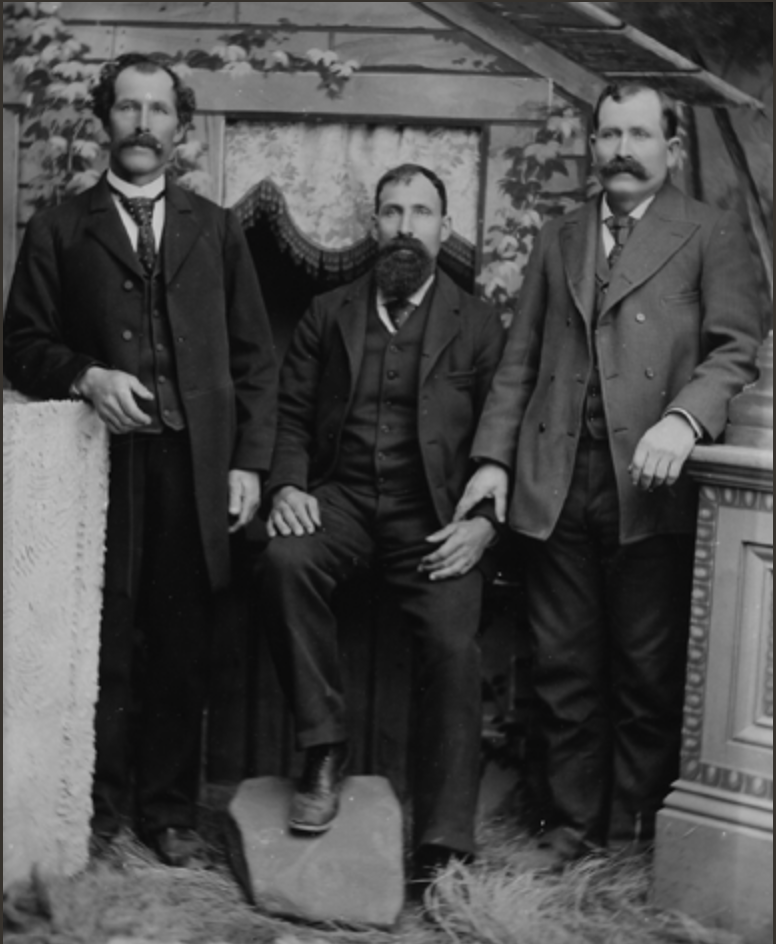

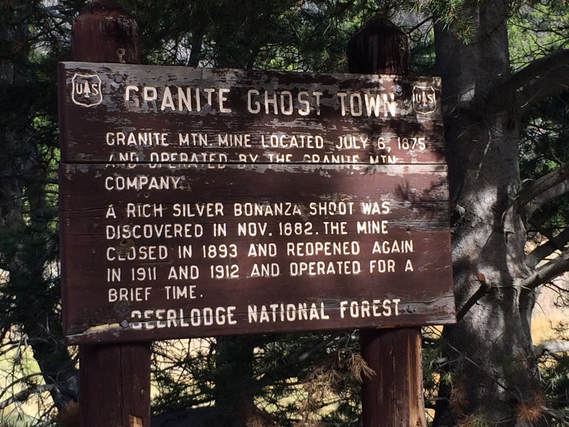

His son Elijah moved to Vermont, where he ran a granite business before relocating to Ohio. David Diaz, an armchair academic, visited some cemeteries in Connecticut and Massachusetts where he found more headstones by the Sikes. Here’s more from Brooklyn, Ct. Addendum Joseph Sikes' mother, Hannah Wright, was a descendant of Mercy Marshfield of Springfield, who you can read about here. Passing near Philipsburg, Montana during my cross-country travels, I stopped to explore the area where my great-great-uncle John Hickey migrated to in 1867 to work in the silver mine. His sister, Elizabeth and her husband, Matthew Reilly, were my great-grandparents who migrated to California before returning to Maine. I had with me an old photo of a log cabin with members of Hickey family standing outside that was taken somewhere near Phillipsburg. Seeking clues, I drove up a dirt road to two ghost town, Kirkville and Granite, that had once been thriving mining towns. I also had a photograph of John Hickey and his two brothers who kept going west to settle in California, John doesn't look like a strong man in this photo, but his obituary described him as an “esteemed citizen” with the nickname “Rock Derrick.” He was the strongest man at Pioneer, a camp of 800 miners, and was capable of lifting and carrying a boulder so large that it required two ordinary men to even turn it over. He reportedly said that any man who wanted to challenge him would have to put up $100 first. No one ever moved the boulder as far as he could and the $100 always ended up at the saloon next door with drinks on the house. “He was a true type of that sturdy manhood that proved such a factor in the development of the west. His doctrine was a square deal for every man and he lived up to it strictly.” Philipsburg Mail, February 17, 1911 -At the Granite County Museum, I discovered that Hickey’s wife, Jane O’Neil, was the daughter of another strong Irishman. Hugh O’Neil was a folk hero who survived 168 rounds in a bare-knuckle boxing match that was covered blow-by-blow by a local newspaper reporter. In her book, “Mettle of Granite County," historian Loraine M. Bentz Domine says Hugh O’Neil was a heavy drinker who would light his cigar with a ten-dollar bill while his children went hungry at home. His eldest child, Jane, had to take charge at a young age. She was reportedly a better muleskinner than any man on the freight line and her language would put any of them to shame. John Hickey entered Jane O’Neil’s life shortly after his arrival to Montana territory in 1867. He was 20 years old, a farm boy from North Whitefield, Maine. According to an interview with his granddaughter in Domine’s book, Hickey first saw Jane when she was a seven-year-old girl playing in Missoula. “He was a real cowboy too – big hat, chaps, even a six-gun on his hip! He picked Mama up and asked her name and age. She told him and he said, ‘Well, Jane, when you are sixteen, I’m going to marry you.’ When she was sixteen her parents had a marriage all arranged for he but before the marriage took place the cowboy showed up again, only now he was a miner.” When Jane and John got married in 1877, they lived in the Georgetown Flats mining camp. John was often gone in the hills prospecting and one time Jane had a premonition of trouble and went to find him sick, without food for days and too weak to get out of bed. In 1884, they built the first family home in Granite at the foot of Whiskey Hills where most of the saloons and “bawdy houses” were located. A year later, the couple lost three of their four daughters to diphtheria within days of each other. When the Catholic priest came to say the girls’ funeral mass, he told Jane that she and her husband must have sinned greatly to have God punish them so severely. At that, Jane left the Church, though John Hickey remained a Catholic. The family moved from Granite to a small cabin in Frost Gulch, a section of Kirkville, in 1888. By the end of the century, Jane had given birth to six more children: Minnie, Kate, John, Ruth, Nora, and Neil. Historian Domine writes that John Hickey worked as foreman at the East Pacific Mine near Winston in 1899, and at the Gallatin mine in Butte. At the time of his death in 1911, he was working a lease at Granite. Hickey’s obituary recounts how every miner in the camp ceased work for the day to attend his funeral and pay a last tribute of respect to a comrade whom all loved and esteemed. The last part of the eulogy was a tribute to the Miner’s Union. “To know him intimately was to be his friend and admirer. There was in the man a nobility of soul that soared among men and the generous heart that beat for justice and humanity… He was always strong, always self-reliant, always sincere. His vision was cosmic and his heart full of love for all mankind.” Philipsburgh Mail, December 29, 1911. Unfortunately, none of John Hickey’s descendants live in the Philipsburg area any longer. But thanks to historian Loraine M. Bentz Domine and her three-volume history Mettle of Granite County, the Hickey’s memory survives.

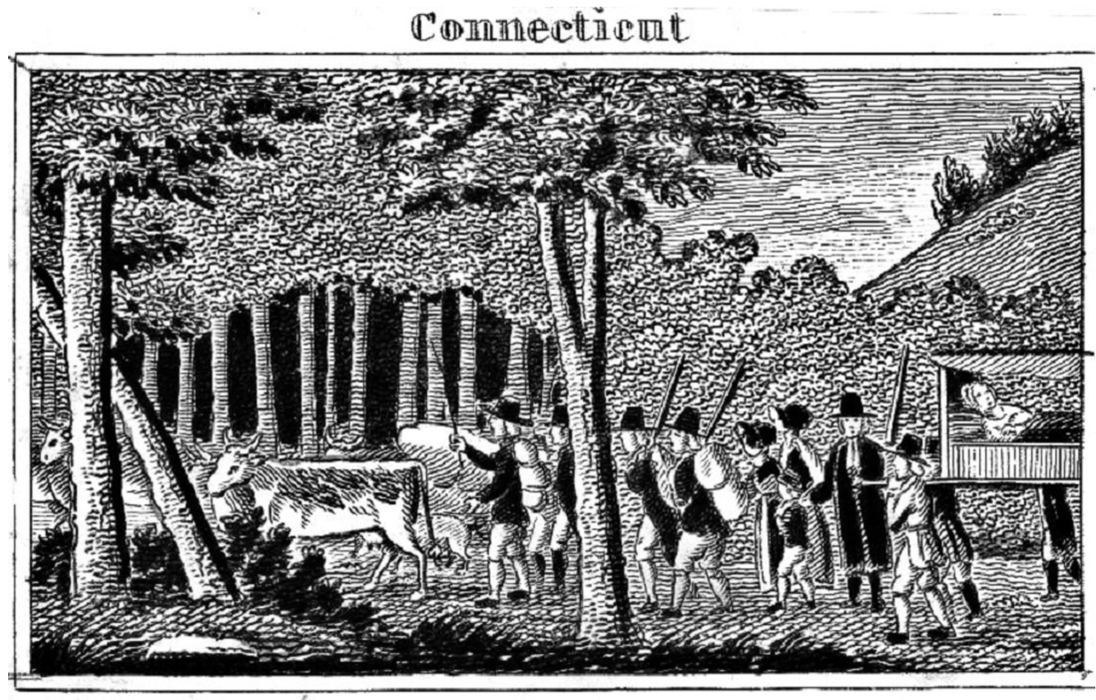

Jane O’Neil Hickey died in 1947. My Marshfield ancestors did not fit the Puritan mold. Thomas Marshfield was not wealthy or educated, but had the wits to engage with those in the social class above him and win their support. Within a year of arriving in Dorchester, in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, he publicly confessed his sins and was embraced by the Puritans. Church membership gave him the right to a land grant and a vote on matters of state. Penniless on arrival, he exploited his new connections and profited – for a while. The Governor of the Colony, John Winthrop, had little good to say about him: "There came in this ship one Marshfield, a poor godly man of Exeter, being very desirous to come to us, but not able to transport his family. There was in the city a rich merchant, one Marshall, who being troubled in his dreams about the said poor man, could not be quiet till he had sent for him and given him £50, and lent him £100, willing him withal, that, if he wanted, he should send to him for more. This Marshfield grew suddenly rich, and then lost his godliness, and his wealth soon after." Gov. John Winthrop's Journal Governor Winthrop took the time to write about my great-grandfather to the 9th removed. That impressed me. Marshfield's public fall from grace must have turned heads back then. The stately Governor uses it to offer a stern warning of the perils that await anyone who strayed from God. The first scrap of clue I found, in a 19th-century history of Dorchester, reported that Thomas Marshfield was a founder of that plantation in 1634, along with other Puritan followers of Reverend John Warham, who hailed from the west of England. Two years later, after banging heads with theologians and political leaders from Boston, members of the same flock picked up stakes and walked east to Connecticut. Thomas’ wife, Mercy, and his three young children now were at his side as they followed Reverend Warham to Connecticut, traveling overland. Walking one hundred miles through the chilly woods in the early spring of 1636, the group would have passed winter teepees circled round the smoldering fires of native camps. The natives did them no harm, watching silently as the newcomers scraped across their ancient paths, yet the unknown must have led the settlers to pray to keep the devil and his savage followers far away. When they arrived at what would become Windsor, the squalid huts of a handful of settlers who had survived the previous winter must have been a sorry sight. Thomas Marshfield received his land grant on a hill above the Connecticut river, a strategic lot that bordered those of the plantation’s most powerful men, the preachers and the merchants. Their first task was to start planting, at least two acres of corn for each member of the household. The Marshfield family was small, only five people, but everyone had to work in the fields. Only a few families – the Wolcotts, the Whitings, the Ludlows – could afford to send servants plant their crops. . Long days planting, weeding and harvesting left Thomas and Mercy Marshfield with little time to build a decent house. Some of the wealthy Puritans shipped pre-cut timbers down from Boston and contracted with carpenters to build sturdy houses for them. The non-endowed settlers lived in rough shelters, some of them scratched out of the river bank. George Francis Dow described the primitive shelters in early Windsor in his book, Every Day Life in the Massachusetts Bay Colony : “The bank itself composed three walls of the shelter and the front was a framing of boards with a door and a window. The roof was thatched with river sedge.” I have no idea what type of housing the Marshfields lived in, tottering as they were on the edge of prosperity, but my guess is that Thomas was too busy trying to establish himself as a merchant to spend much time building a house. He presumably had to donate labor to construct fortifications to protect the Puritans from outside attacks in fulfillment of an obligation that was paramount. It is unclear how Thomas Marshfield managed to build his reputation as a merchant given that the beaver trade and any trade with the Indians was granted to only one person in each plantation. For the next four years Thomas sought out investors to finance the procurement of two ships in England to start a trans-Atlantic trade. He found a willing partner in Henry Wolcott, a wealthy landowner and Puritan who backed many ventures in the new plantation, and with Samuel Wakeman, who was already involved in the trade. Thomas left Windsor in 1640 and sailed to Bristol, England, where he chartered the ships Charles and Hopewell. More than a dozen merchants had signed up to ship good with him back to Boston. Then, plans started to go awry. The ships sailed behind schedule and with insufficient food, water and spirits onboard. The crew of the Hopewell was said to be rowdy heathens, tormenting the Puritan passengers onboard. After the ships docked in Boston, many charged that Marshfield had deceived them all. By 1642, more than one dozen claims had been filed against Marshfield in the General Court of Connecticut. Henry Wolcott switched from partner to plaintiff, charging that Marshfield owed him 40 pounds. Wolcott also represented other claimants from Boston while Wakeman, the third partner, was shot and killed in the Caribbean, outside the Puritan settlement on Providence Island. Amid the turmoil, Thomas Marshfield vanished, with no record that he ever returned from England. The court case went on without him and when it was concluded in 1643 with the seizure of all of the Marshfield family property, including their house, land and household goods. Mercy and their three children, Samuel, Mercy and Sarah, were left penniless. Despite his tarnished reputation, Thomas' named was not erased from Windsor history, where he is honored as one of the founders of the town. The Marshfield story does not end here and the next chapter has a few surprises, too! Stay tuned. How is Thomas Marshfield related to me?

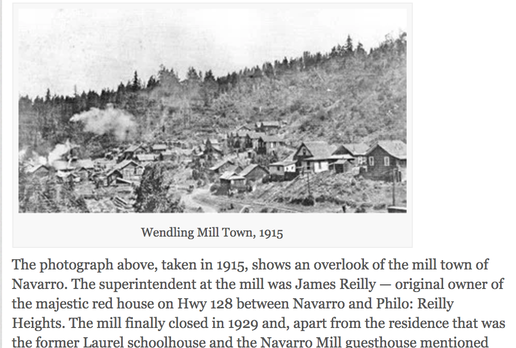

His daughter, Mercy, married John Dumbleton in 1650 and their daughter married Thomas Merrick. Chasing the line of their descendants from central Massachusetts to Maine, you find Sara Sykes, a Protestant who married Irish Catholic John Hickey in 1842. Sarah's grandfather was the renown gravestone carver, Joseph Sykes. The Irish on my mother’s side defined their community around St. Denis’s Catholic Church in North Whitefield, Maine, where James O’Reilly was one of more than a thousand Irish immigrants who settled there by 1832. The O’Reillys could be counted among those who left Ireland decades before the potato famine that pushed a million hungry refugees to the United States. In Maine, the Irish worked the land. (In the mid-1800s, they dropped the O before Reilly.) My mother is a Reilly and my father is already buried at St. Denis church, her name etched into his stone awaiting an end date. She feels most at home here. I don't know when James married Mary Kavanaugh, who was born in Ireland around 1817. Their first child was born when she was 22. Of significance in this story line, my great-grandfather, Matthew Reilly, her fifth son, was born in 1847 in a rambling farmhouse in North Whitefield, Maine, one of those ingenious buildings with an attached barn so you never have to venture into the cold to use the outhouse. After a rudimentary education, his two sisters worked as domestic servants while his father and three older brothers joined him to farm the rocky soil on their farm. By the time the Reilly brothers were in their late 30s, America was connected by a railroad and the lure of California glistened. By the late 1880s, the Reilly brothers and their families set off to find new opportunities out West. They joined some 200 men living in a logging camp, cutting and hauling trees to the lumber mill. James and Joseph prospered in the Navarro mill; James eventually became its superintendent but Matthew, the youngest of the boys, dropped his California dream and returned to Maine, taking his family with him. Family tradition claims that he left to care for his elderly mother after his father’s passing in 1891. Matthew, and his wife, Elizabeth Hickey Reilly, took portraits before they left California. A well-worn photo of my grandfather Maurice, wearing knickers and staring unflinchingly into the camera, was taken in Mendocino before they departed. As they traveled, my 8-year-old grandfather must have spent hours staring out the train window, mesmerized by the vastness of the west. Did the dry, flat monotony of the desert, lifeless and hot, animate what he had been taught of the horrors of hell? After witnessing the towering peaks of the Sierra Nevada mountains, could any peak in Maine ever slow him down? I can see the train chugging past Nebraska farmland, its fertility holding the promise of more. Once he returned to Maine, Maurice proved restless, always on the move, a consequence, perhaps of recognizing the vastness of the world on that cross-country trip. With his wife and five children, my great-grandfather Matthew resumed the farm life and blended back into the Irish Catholic parish. When a daughter entered the convent and emerged as Sister “Kate” Ignatius Loyola, it must have been a moment of pride. Sister Kate was my great-aunt. My grandfather, Maurice, was still studying in school when he turned 16 in 1900, He studied the popular Century Book of Facts and learned enough to get a teaching position in a neighboring community. My mother told me he walked nearly 20 miles from his home in Whitefield to Head Tide every week, renting a room in the village while he taught school. (Seventy years after Maurice taught in Head Tide, my mother, Catherine Reilly Peckenham, and her husband, Thomas Francis Peckenham, bought one of the oldest homes in the hamlet, Spring House.)

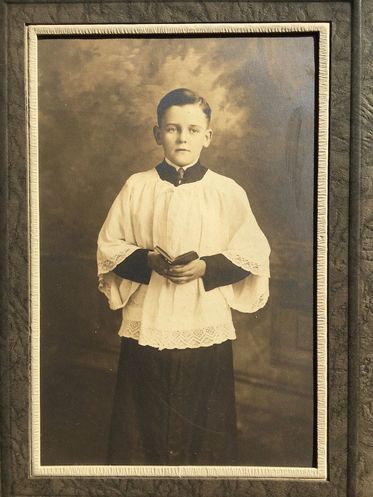

One of my grandfather's earliest jobs was as a clerk sorting mail on the train from Bangor to Boston. The work sounded romantic to me and only later did I learn about its dangers. Tossed around in old wooden postal railways cars, more than 50 clerks a year were killed or injured every year at the turn of the century. My grandfather survived. He lived in Gardiner, Maine, where he wooed and then married a cultured, educated woman. His family back in Whitefield must have been stunned by the news that he had married a Protestant Yankee, Mattie Belle Eldridge. The Irish Catholic Church loomed large in the lives of both my parents and shaped who I am today. In my childhood, my ancestors appeared to me as soft gray forms that we prayed would make the transition from purgatory to heaven above. The elderly who were still living had only a bit more life force. I can still feel the shadow of my widowed grandmother hovering in a few early childhood scenes. Every Sunday, my father would drive the family 20 miles to Manchester, Connecticut, to pay his respects to his mother, Mary Jane Donnellan Peckenham, a proper Irish lady who kept an eye on her neighbors from behind lace curtain, and his aunt. It was dark and stuffy inside their house on Elro Street and, if we were lucky enough to be offered cookies, had to eat them daintily to avoid dropping any crumbs. No hugs or tickles from this grandmother, a frail woman with frail wireless glasses and grey hair in small, tight curls, who looked like she had never outstretched her arms to anybody, my father included. Mary Jane, and her unmarried sister, Margaret, daughters of Irish immigrants, worked at Cheney silk mill in Manchester most of their adult lives. Mary Jane was a weaver and Margaret, a clerk. Mary Jane was 37, well past her prime, when she married a handsome Irish bachelor in 1914. Thomas Francis Peckenham was the son of Irish immigrants who settled in Providence, Rhode Island. Born in 1870, Thomas was still in Rhode Island in 1900, when he was elected as an officer of the Knights of Columbus, a fraternal Catholic organization. A decade later he had relocated to Manchester, Ct., where he worked as a mason in an aircraft plant and was active in his union. Thomas was elected a justice of the peace in 1914, the same year he ran for a seat in the Connecticut state house and lost. My grandfather Thomas Peckenham married well past the prime of youth. He was 44 years old at the time of his wedding and became a father three years after that. In addition to his civic involvements and mason work he also worked as a security guard in the Colt Firearms plant in Hartford. He led his little family until he died of pneumonia in 1930, when my father was just 13. Though young, my grandmother and her sister no doubt prayed that little Francis, my father, would assume a man’s role at home. He had been trained by the church to be a faithful son. By my father’s own confession, he was a poor student but in the midst of the Great Depression, he managed to work and give a portion of his pay to his mother. When he was an old man, my father swore he had no memories of his father but I suspect the few memories he had were too painful and reminded him of his loss. In front of us, he put his mother on a pedestal. After she died in 1960 whenever he uttered her name and quickly added, "may God rest her soul." Did he worry that the woes she faced in her lifetime still troubled her in the afterworld? Irish pride in relatives who had joined the Catholic clergy or monastery was rampant when we were kids. My father drove us clear across Connecticut to pay our respects to his cousin, Sister Trinita, who smiles coquettishly in a photo we still have of her as a young girl named Mary Louise Mahoney, long before she entered the Franciscan order. I still get a shiver when I think of entering the Gothic grey convent where she lived and seeing her float towards us down the high-windowed hallways of the convent, her white habit billowing as she glided along. On those days, I didn’t speak, my jaws snapped shut in awe. Later in life, my father thrilled to learn of a distant cousin in Ireland, Father Michael Pakenham, who was a village priest. A portrait of him that hung in the family home back in County Leitrim, Ireland somehow made its way to America when it hung in my father’s office. My father tried to cement our Irish Catholic future when, after serving in World War Two and surviving, he set out to find an Irish lass that his mother would approve of, unaware of how high that bar was. He found a sweet girl in Waterville, Maine, a school teacher and a respected Irish Catholic to boot. He married my mother, Catherine Agnes Reilly, the next year.

|

Names of My AncestorsPuritans & Servants Archives

February 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed