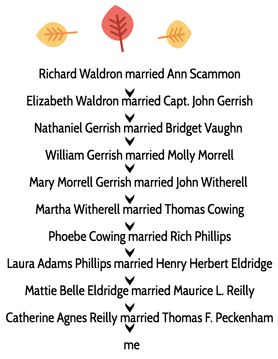

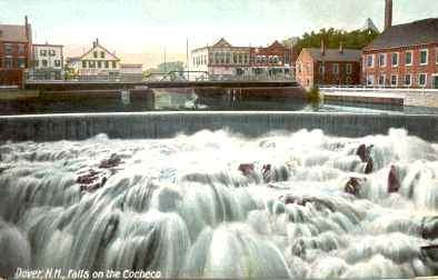

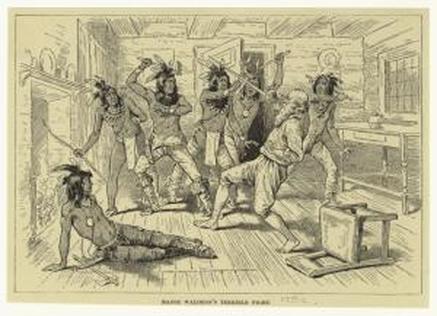

I had hundreds of people in my family tree already, enough to keep me busy tracking down ancestral profiles for years to come. I did not need to find Richard Waldron in my bloodline, but when I did, all the angst of responsibility for the actions of my ancestors flooded back. Must my life create a thousand acts of contrition to erase the legacy of such a man? Richard Waldron came from the group of Puritans who put their family fortunes to profit in the Massachusetts colony. He came first to Boston in 1635 and for two years surveyed and purchased land. He returned to England, married, and returned to settle in Cocheco, now Dover, New Hampshire, where he built a sawmill and a gristmill on the river, along with a trading post, where Native American traders suspected him of cheating them. Within 15 years of settling in Dover, Waldron had three children and his prominence in the Massachusetts Bay Colony kept rising. Elected to the General Court of Boston in 1654, he served for nearly 25 years, some as speaker of the house. Punishing the Quakers Waldron also earned a reputation for harshness when, in 1662, he ordered constables in eleven towns from Dover to Boston to tie three Quaker women to a cart and whip their bare backs publically. In the depth of winter, through snow, the women were marched to Hampton where they were whipped. In Salisbury, the local constable, Sgt. Major Robert Pike, balked at Waldron’s order then sent a team to intervene and bring the women to safety on the other side of the Piscataqua River. The poet John Greenleaf Whittier portrayed the Quaker persecution, depicting how the Quaker women might have cursed him: "And thou, O Richard Waldron, for whom In 1672 Waldron was commissioned a military captain, then major-general in the province of New Hampshire. He led the failed campaign against the French and Indian raids on English settlers on the coast of Maine and in Acadia in 1676 and had frequent dealings with the local Pennacook Indians, who remained neutral during the King Phillip War. Yet, with hostilities all around them, the people of Dover lived in homes that were barricaded like garrisons. After the King Phillip war ended, dozens of the warriors who fought the British took refuge with the Pennacook Indians. Waldron was ordered to seize all the outside warriors but he had instead proposed inviting the men to a military game event in Dover where he tricked them out their weapons. Once captive, the wanted men were separated from the Pennacooks and taken prisoner., two hundred men in all. Eight of them were executed and the rest sold into slavery, an offense that the Pennacooks would not forget. Thirteen years later, the Pennacooks, now under a new leader, took their revenge. In an well-planned move in June of 1689, they sent Penacook women to ask for overnight shelter at the five garrisoned houses in town. It was a rainy night and all but one of the women were allowed in. After midnight, the women slipped the bolts and opened the door to the revengeful Pennacooks. The slow torture and death of Richard Waldron is not one for the weak of heart. Reports say he tried to defend his household with his sword but was quickly overcome. His head was split open and his bleeding body tied to a chair in the main room. Pennacook men took their time with him, each cutting an X into his chest to signify their trade accounts with him were closed. Still alive, his ears and nose were chopped off and stuffed in his mouth. When he had little life left, his tormentors rigged his sword so he would fall on it and deliver the final death blow. Other members of his family were killed and his house burned to the ground. His six-year-old granddaughter, Sarah Gerrish, was taken prisoner. Waldron’s daughter Elizabeth Gerrish was safely at home with her husband and her other children, including nine-year-old Nathaniel Gerrish, my direct ancestor. In all, 23 people were killed and 29 captured that day in Dover. Waldron’s son and grandsons rose to great prominence in the state of New Hampshire and are now part of the legacy of the Granite State.

Richard Waldron's grandson, also named Richard, was a prominent political leader of colonial New Hampshire in the 1730s and 40s. He is not directly related to me. Here's his portrait

5 Comments

Richard Waldron

9/18/2021 10:24:09 pm

Haven't been able to trace a direct line to the Major. My oldest known ancestor is one Daniel Waldron, born in 1733. He and his wife Freelove Waldron were the parents of one Isaac Waldron of Oyster Bay, New York. Isaac married Phebe Hauxhurst and had sons, one of whom passed down my name to me.

Reply

Kathleen Blake

3/14/2022 01:12:14 pm

I have been doing research on Richard Waldron. Please email me. I would really like to share what I have found with you, and a project that I hope to complete. Thank you.

Reply

Nancy Peckenham

3/16/2022 06:04:06 pm

Hello Kathleen. I don't know if you will see this response but you can email me at [email protected]

Reply

Kristina Dube

8/24/2022 03:51:04 pm

I would also Love love love to get in touch with you as I am as well doing a project that features Mr. Waldron and the infamous Sham Battle. I've been trying to hunt down a credible source that knows where exactly it occurred. I'd love to share sources if you have any!

Patrick O. Connelly

1/20/2023 09:30:02 am

The upcoming History of Rochester N.H. contains primary source documentation from the 17th C that debunks the event giving rise to the aggravated animosity felt by the native Abenaki against the major. Discussion at 727-639-7754

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Names of My AncestorsPuritans & Servants Archives

February 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed