|

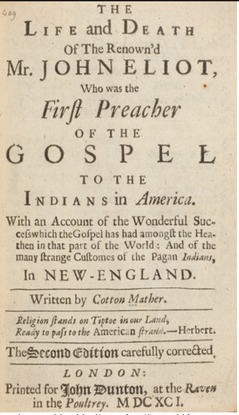

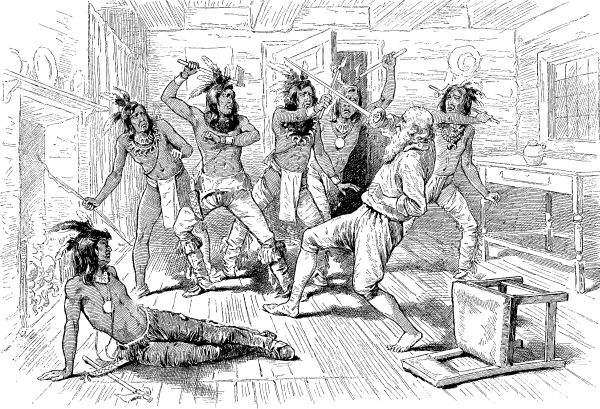

More than 300 years ago in northern New England, a seven-year-old girl was kidnapped by Native Americans who held her captive in the wilds of Maine, then forced her to march to Quebec, Canada in the dead of winter. Sold to the French, the young girl was eventually returned to her home in Dover, New Hampshire. The tale of Sarah Gerrish, my 7th-great aunt, was told throughout Boston where the Puritan leader, Reverend Cotton Mather, used it as a stark warning about the dangers of Native Americans and Catholics. Gerrish’s experience featured a classic Puritan captivity narrative, in which “a single individual, usually a woman, stands passively under the strokes of evil, awaiting rescue by the grace of God. The sufferer represents the whole chastened body of Puritan society.” (Richard Slotkin, Regeneration through Violence, 1973.) Sarah’s Story One rainy June night in 1689, Sarah Gerrish was sleeping in the fortified garrison of her grandfather, Richard Waldron, the most powerful man in the frontier outpost of Dover, New Hampshire. She was innocent of her grandfather’s misdeeds, which included double-crossing the Pennacook tribe 13 years earlier. The Pennacooks took their revenge in the nighttime raid when they tortured Waldron then killed him, most likely in front of his granddaughter. (Waldron’s story is told in full here.) The raiders killed 23 settlers and took 29 captives, including Sarah, who was rushed out of the garrison with time to put a stocking on only one foot. Walking barefoot through the woods of Maine was the least of the hardships Sarah would face over the next several months. According to the report sent to Cotton Mather in Boston by Reverend Pike in Dover, Sarah was first held captive by a sachem named Sebundowit, who later sold her to another sachem who Mather described as “a more harsh and mad sort of dragon.” For six months, Sarah was held in Maine and Mather reported two incidents of psychological terror. “Once her master commanded her to loosen some of her upper garments and stand against a tree while he charged his gun. The poor child shrieked out: ‘He is going to kill!’ But instead he warned her and let her be.” On another occasion, her captives built a large fire and told her she was to be roasted. She burst into tears, threw her arms around her master's neck and begged him to save her, which he promised to do if she would behave well. She survived a near-drowning when pushed into a river fully clothed by some Native American girls and at some point she realized that she would likely die if left alone in the deep woods. One morning she overslept and the Native Americans had picked up camp and left her behind. With snow on the ground and no food, she tracked her captives and rejoined their ranks. When the Native Americans holding her reached Quebec, Sarah was sold to the wife of the French Intendant, who put her in the nunnery. The nuns were said to have adored the young girl and to be saddened when she returned home. After less than a year in Quebec, a British attack against the French city fort failed and in the ensuing exchange of prisoners, Sarah Gerrish was turned over and sailed to Boston. She was reunited with her family, the Gerrishes, in Dover. She died eight years later at the age of 16 and her story lived on as an example of how a devout Puritan can overcome evil in life.

3 Comments

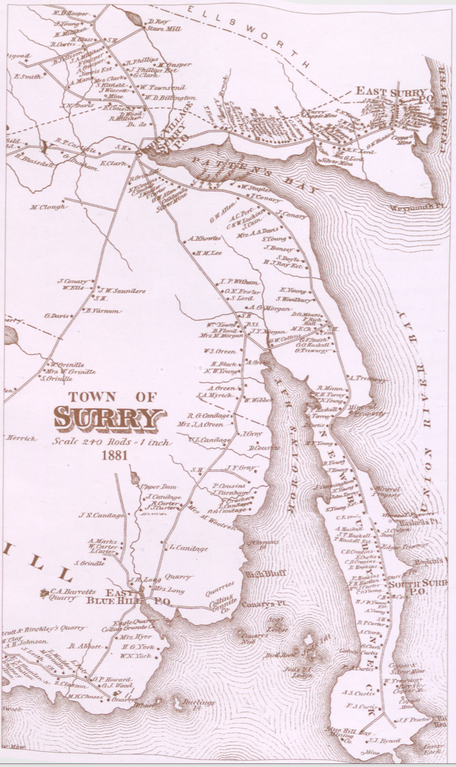

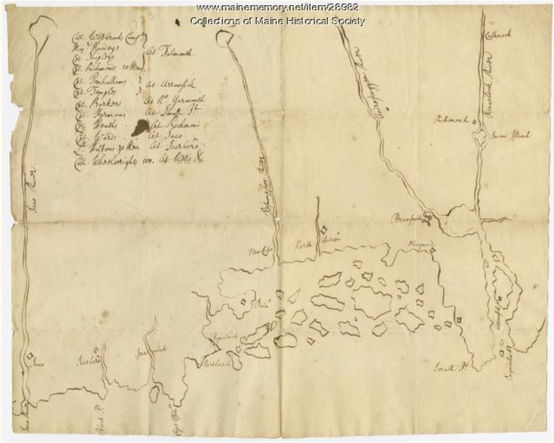

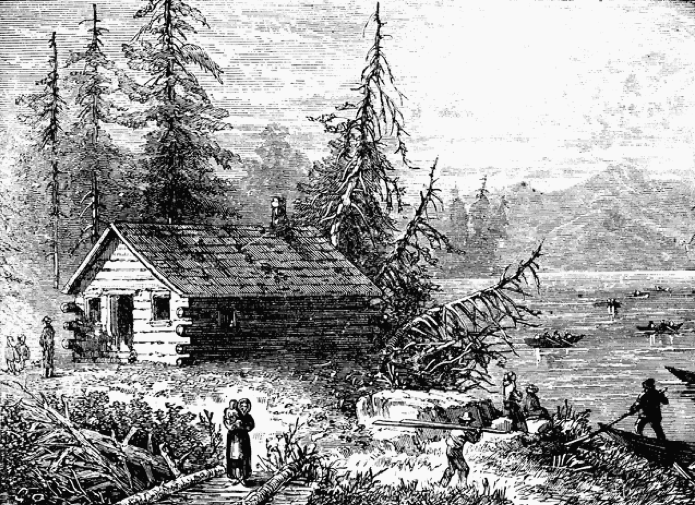

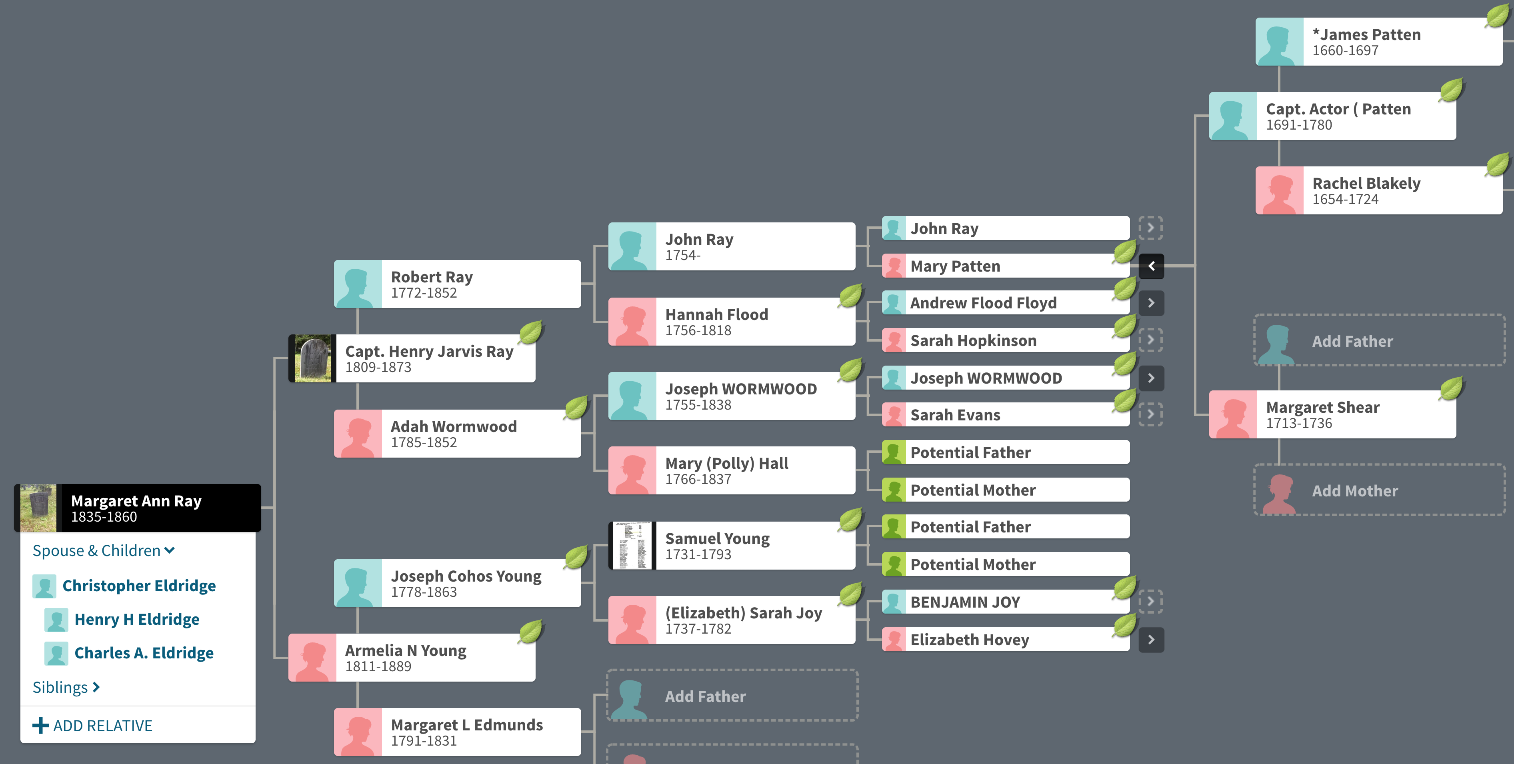

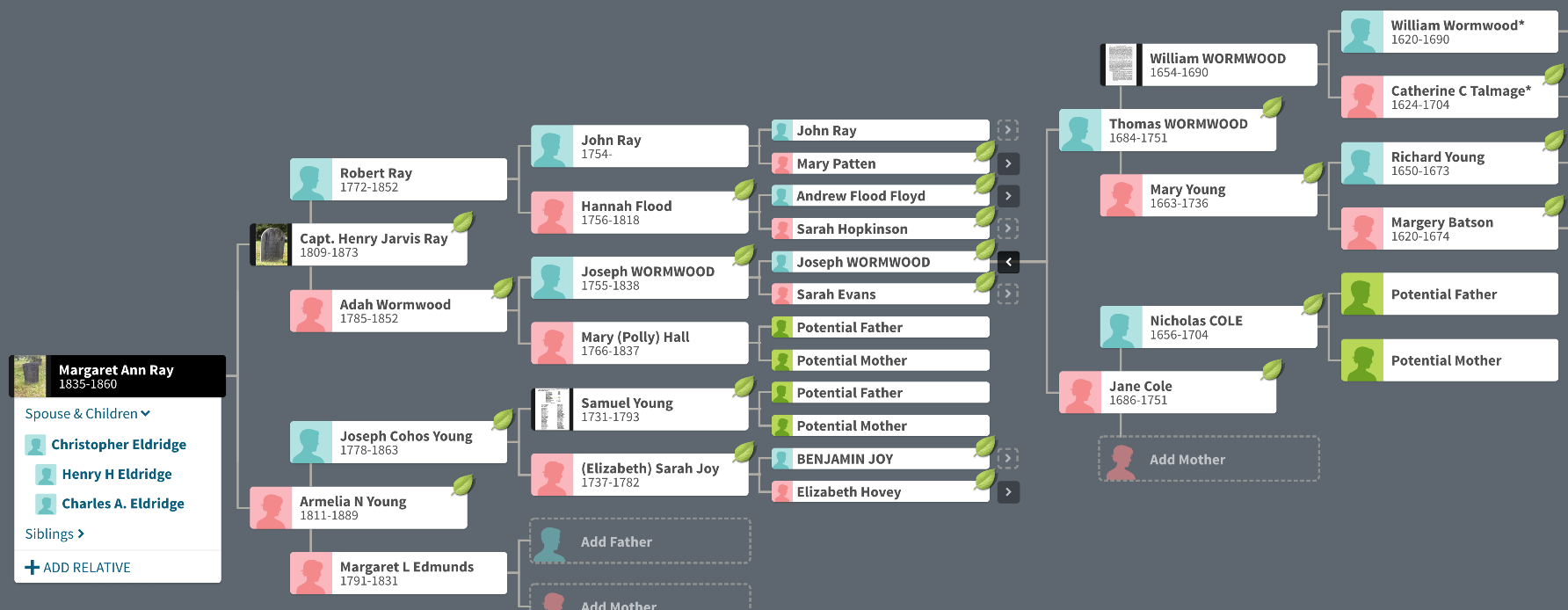

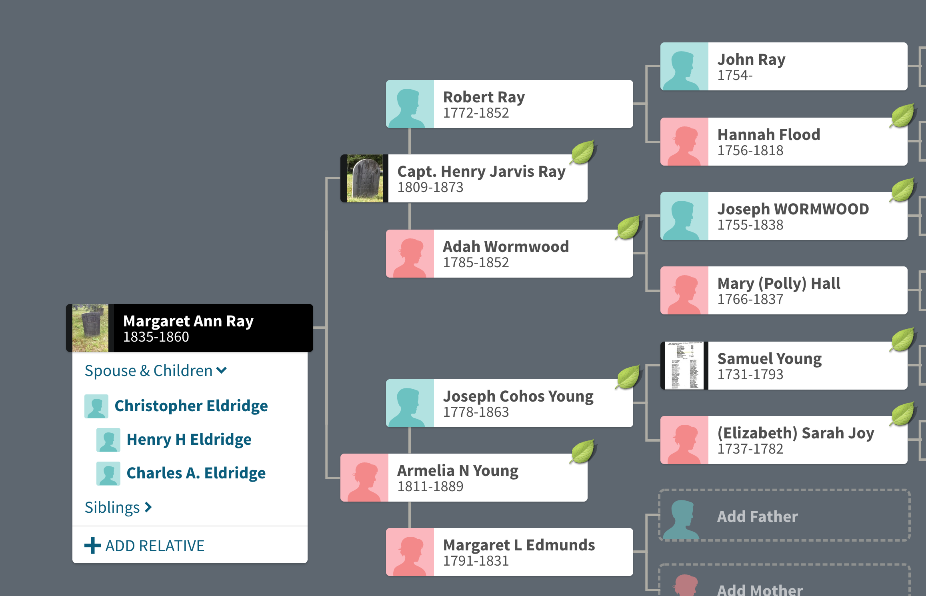

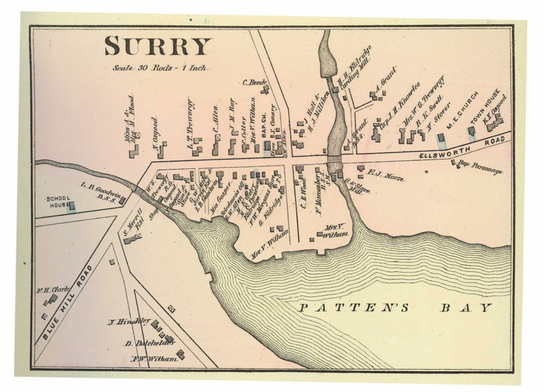

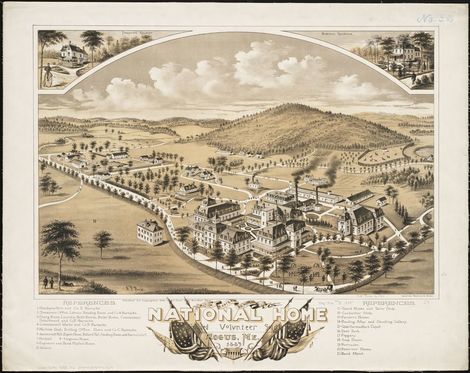

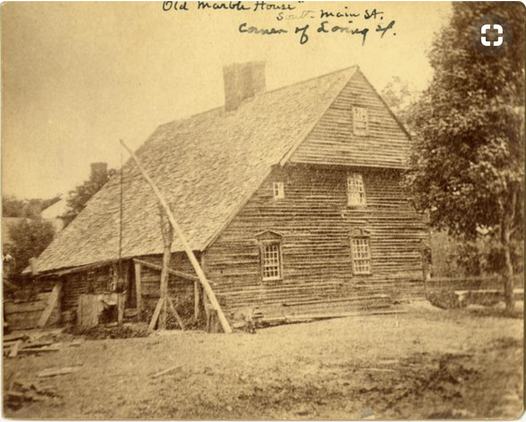

The Surry area just northeast of Blue Hill, Maine, is a place that has occupied a corner of my mind since I first learned my grandmother was born there. It was always a magical place on the Downeast coast with an old farmhouse that provided a clear view of Mount Desert Island. My picture of heaven. A grey-shingled farm on Newbury Neck in Surry is the home where my grandmother, Mattie Belle Eldridge, was born in 1883, one of five children of Henry Herbert (H.H.) Eldridge. His grandfather had moved to that town in the 1840s. (Read their story here.) As I dug into the history of the 18th-century coastal township that became Surry, I learned the Eldridges arrived some 80 years after the first colonial settlers to the area identified as Township No. 6. This does not include attempts by French settlers, priests and military men to establish outposts along the coast or, of course, the Wabanaki Native Americans who had lived there for thousands of years. Downeast Maine had been a backwater of Massachusetts until the 1760s when migration accelerated northward. The commonwealth of Massachusetts encouraged new settlements that would help the British establish control of the area at a time when the French were claiming portions of the coast. General Pownall came to the Penobscot River in 1759 with 400 men to build a fort near present-day Stockton Springs. Enterprising settlers, driven by lack of land or to exploit the area’s natural resources, soon followed. Matthew Patten, my 7th-great-uncle, is reported to have been the first to settle in Township No. 6, followed by Andrew Flood, my 6th-great-grandfather. By the mid-19th century Surry was a bustling town, with mills and a shipyard that produced some 50 ships. Many young men went to sea in this era and many never returned. Seeing the same hills, rivers and byways that my ancestors populated helped me piece together a picture of their 18th-century world. I started with my 2nd great-grandmother, Margaret Ann Ray, whose gravestone stands largely untarnished in Morgan Bay Cemetery on Newbury Neck in Surry, a tangible, touchable link to those who came before her. The Young Family Tracing back through Margaret Ann Ray’s parentage, I found a broad array of people who settled in the Surry area by the the 1790 census. Chief among them is Margaret Ann Ray’s great-grandfather, Samuel Young. (Read the full story of Samuel Young’s family here.) Samuel and Elizabeth Young’s son, Joseph Cohoes, married Margaret Edmunds and their daughter, Armelia Young, married a sea captained name Henry Jarvis Ray. The Ray Family

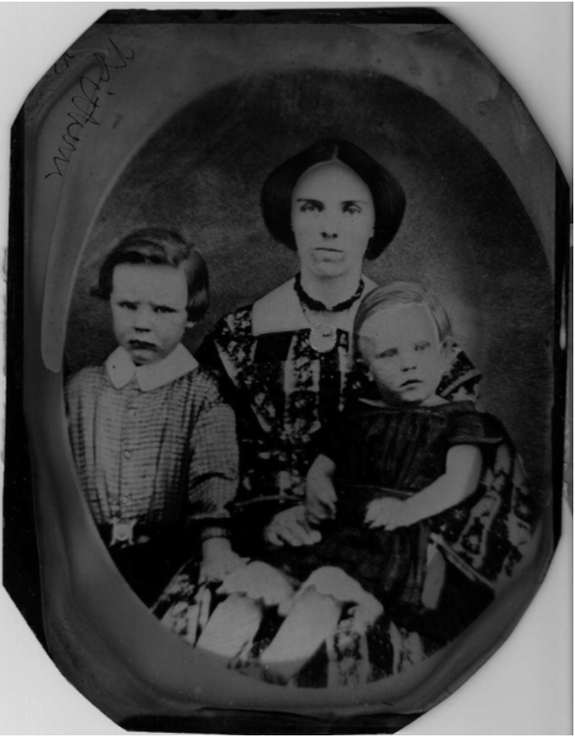

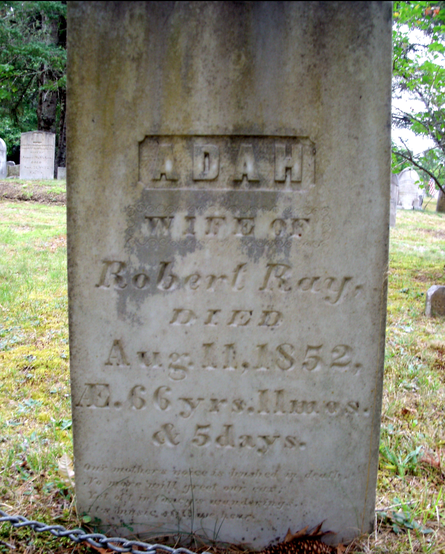

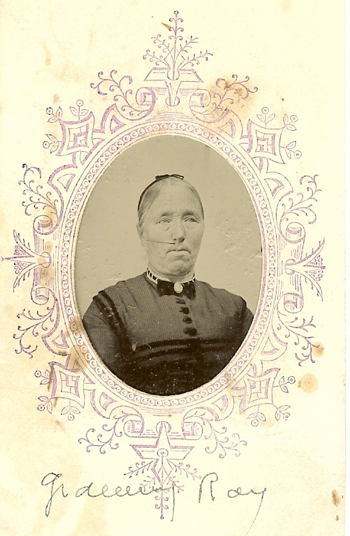

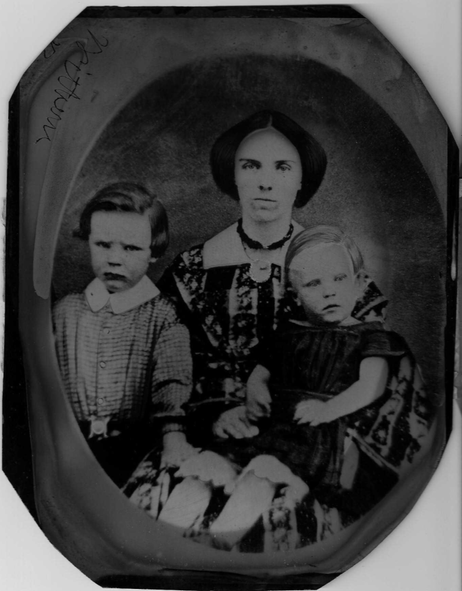

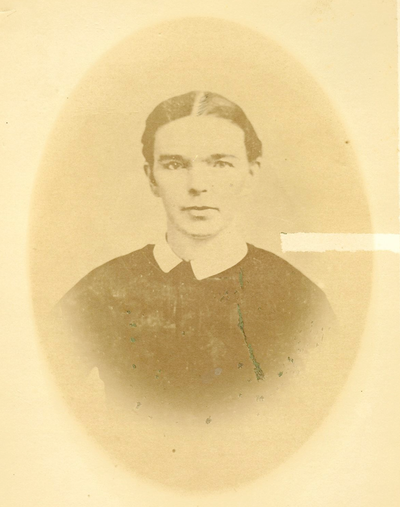

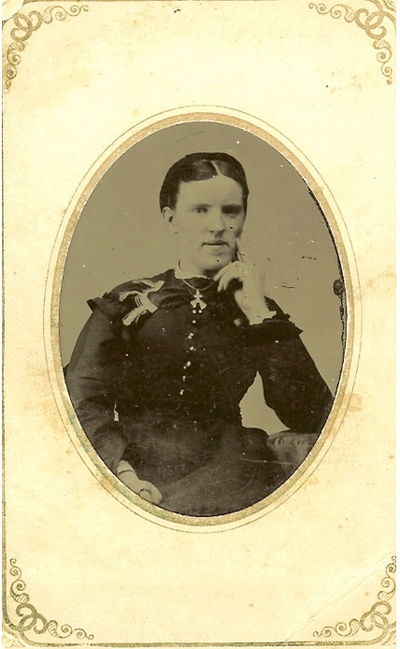

In 1852, Armelia and Henry Jarvis Ray’s daughter married Christopher Atwood Eldridge, whose father had moved the family to Surry a decade earlier. By 1862, both Christopher and Margaret were dead and their two young sons, my great-grandfather and great grand-uncle, went to live with their grandfather, Knowles Godfrey Eldridge. The Ray family, it turns out, arrived in Maine as part of a wave of immigrants that moved from Scotland to Northern Ireland before bringing their Presbyterian beliefs to Boston in the early 1700s. These beliefs clashed with the dominating Puritan church and many of them moved north, including the Rays and the Pattens. (Read the full story of Margaret Ann Ray’s Scots-Irish parentage here.) The Wormwood Branch A final, but noteworthy, branch of the Surry family is made up of the parentage of Robert Ray’s wife, Adah Wormwood. Adah was born in 1785 in Surry, the daughter of Joseph Wormwood. Joseph migrated to Township No. 6 from Wells, Maine, an area where his ancestors had landed nearly 150 years earlier, in the 1630s. Adah Wormwood’s birth, it turns out, was a result of some simple twists of fate. Her grandfather was alive after surviving a winter shipwreck while her great-grandfather had his own brush with death. The Wormwood’s family dramatic story starting in Kittery, Maine in 1639 can be read here. Today in Surry the descendants of the Youngs and the Rays are scattered along quiet country lanes. I don’t know any of them but my research has attached all of these people to a huge, spreading family tree. A When I dug into the background of my maternal 2nd-great-grandmother, Margaret Ann Ray, Eldridge, who was born in Surry, Maine in 1835, I discovered the Scots-Irish branch of my family tree who arrived in Maine in the early 1700s. The rest of my ancestors who settled in Surry were English but Margaret Ann Ray was the descendant of two Scots-Irish families who brought their Presbyterian faith and reputation for physical strength and tenacity to Maine. They came to New England some one hundred years after their ancestors fled Scotland to Ulster, Northern Ireland, with the support of the British crown, which hoped to use them as a buffer against the Irish Catholics to the south. By the early 18th-century, high rents, famine and smallpox made life unbearable in Ulster and over the next 75 years, some 200,000 Scotch-Irish came to the American colonies. An early group of more than 300 Scots-Irish from the River Bann Valley of Ulster arrived in Boston aboard five ships in early 1718. They had negotiated with local officials to receive land grants on arrival but the Boston Puritans spurned them for their different religion and culture. Many of the families headed north and settled in Nutfield, later named Londonderry, New Hampshire, where they introduced potato and flax crops. A smaller group sailed to Casco Bay, off present-day Falmouth, and spent the winter onboard ship, freezing. Of those families, a few stayed in the Falmouth area while others headed south to the Merrimack River. Over time, others settled along the remote Maine coast where they found fertile pieces of land to farm. Margaret Ann Ray’s ancestors were in Biddeford, Saco, and on Flying Point in North Yarmouth, later Freeport, Maine. Another group of Scots-Irish organized by Robert Temple, a former British army officer, settled in the Georgetown and Merrymeeting Bay area, near the Kennebec river, in 1718. British colonists had just built a fort at the mouth of the river, defying Native American Wabanaki claims to the territory and hostilities soon followed. Attacks were encouraged by the French who came down from Quebec to pursue their claims to the territory, supplying the Wabanaki with arms to use against the British and Scots-Irish settlers. Numerous killings and kidnappings drove many settlers to abandoned the area by 1722. By 1725, the Wabanaki had been weakened and they retreated north, allowing the original settlers to return and new arrivals to join them.. We don’t know exactly when the Ray family arrived, though many amateur genealogists have reported that John Ray was born in North Yarmouth about 1728. In 1753, Ray married Mary Patten, in Biddeford. She was the daughter of Hector Patten, another Scots-Irish man who migrated from Londonderry, Northern Ireland, to Boston, then to Falmouth and Purpoodock (Cape Elizabeth) around 1730. Mary Patten was born in 1733 in North Yarmouth, the same place where the Ray family was apparently living. Her mother was Hector’s second wife, Margaret Shear, who died shortly after her birth. Hector Patten and his third wife, Mary, moved to Biddeford in 1739, where he bought forty acres of land. In 1751, He was identified as a “yeoman alias mason,” and his life was largely unremarkable, save for his acquittal on a charge of not attending religious services. The Pattens and the Rays Migrate Further North After their marriage, my direct ancestors, Mary Patten and John Ray, remained in Biddeford, while Hector Patten’s family migrated northward. In 1754, Matthew Patten, Mary’s brother, bought farmland in North Yarmouth, and his parents moved with him. Around 1762, Matthew had moved north to the new frontier of Township No. 6, now Surry, where he is recognized as the first settler. His parents joined him there. Hector Patten died in 1782 and is buried in Surry. John and Mary Ray were said to have died in Biddeford and we don’t know when, or even if, their son, John Ray (born 1754), joined both Patten and Ray relatives who had moved to Township No. 6. He married Hannah Flood, the daughter of early Surry settler Andrew Flood, in 1772 in an unknown town in Maine and his wife gave birth to Robert the same year. Hannah and John’s union was not destined to survive long. Four years later, Hannah married another man, James Patten, though John was still living. John Rae (Ray) was identified as living across the bay from Surry, on the east side of the Union River, where he was one of two members of the Revolutionary War’s Committee of Correspondence that sent a letter dated August 6, 1776, asking for arms. John Ray’s name does not appear in the 1790 census of Surry, though his brothers Matthew and James both do. Robert Ray, John and Hannah’s son, settled in Surry and prospered. His son, my 2nd-great-grandfather, Henry Jarvis Ray, was a farmer, like his father. According to the Biographical Review, Robert Ray, was born and reared in a coastal town of Maine and after his marriage to Adah Wormwood, settled in Surry. “Having bought a tract of unbroken land on the Shore Road, he cleared a part of it, and for a time tilled the soil. He subsequently sold that property, and purchased land on the Bay Road, on which he was engaged in general farming and lumbering until his death, at the advanced age of seventy-nine years. His wife died at the homestead in the sixty-sixth year of her age.” Henry Jarvis grew barley on his farm on Newbury Neck in Surry and grazed eight sheep and other livestock on 67 acres. By the time he was 61 years old, in 1870, the livestock was valued at $198. One of his sons, Jesse Ray, became a prominent citizen and served in the state legislature. Owner of a grist mill, the Henry C. Wood Company, he built the Surry Village School in 1872 for $2,000. Henry Jarvis’s oldest child, Margaret Ann, married Christopher Atwood Eldridge in 1853 in Surry. The couple moved into a house near the shipyard in Surry, right next door to Christopher's father, Knowles Godfrey Eldridge. Seven years after they married, Margaret Ann died at age 24, leaving two young sons, Charles and Henry Herbert. Christopher Eldridge died two years later and the boys were orphaned, going to live with their paternal grandfather, who manufactured clothing in Surry. Throughout their lives the Eldridge boys held on to a faded photo, a memory of their maternal grandmother, Armelia Young Ray, the wife of Henry Jarvis. Discover more about this topic in Scotch-Irish in New England by Rev. AL Perry, Professor of History and Politicis Wiliams College, Williamstom, Masss. Taken from The Scotch Irish in America: Proceedings and Addresses of the Second Congress in Pittsburgh, Penn. May 29-June1, 1890.

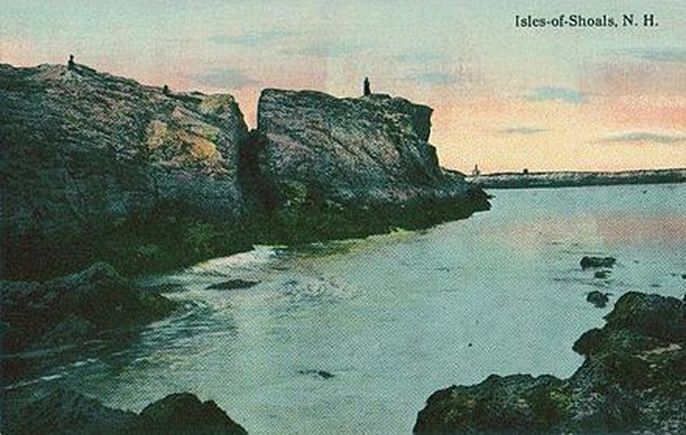

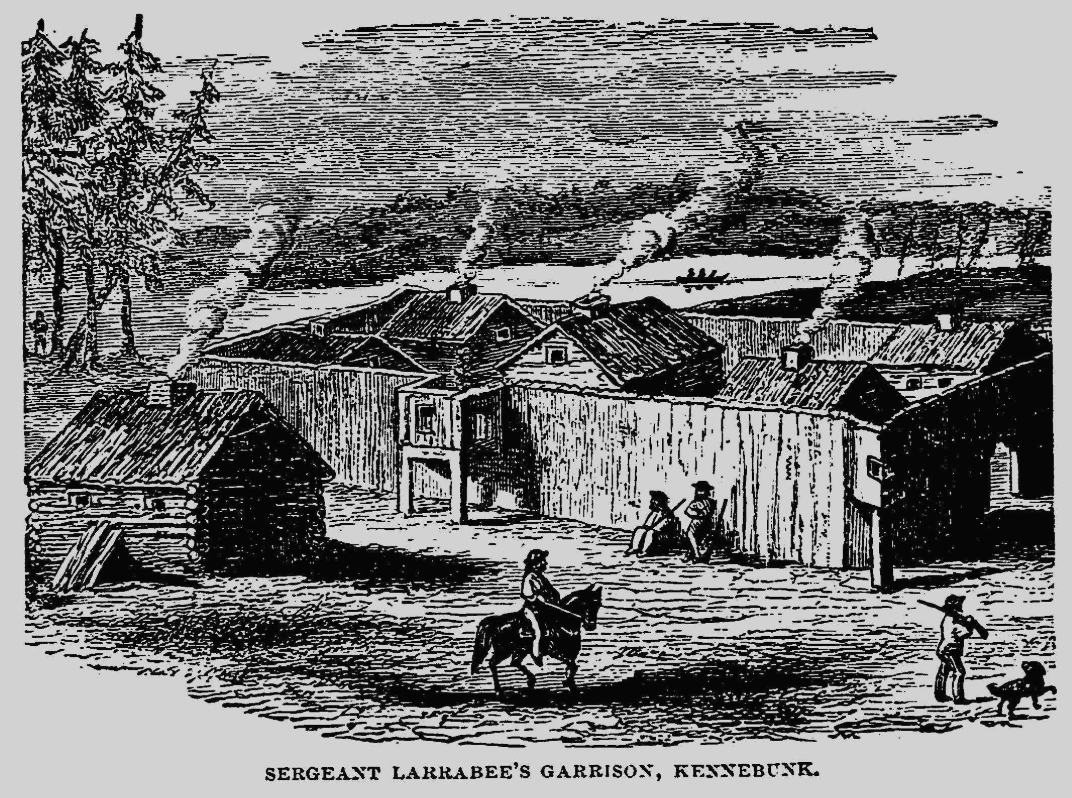

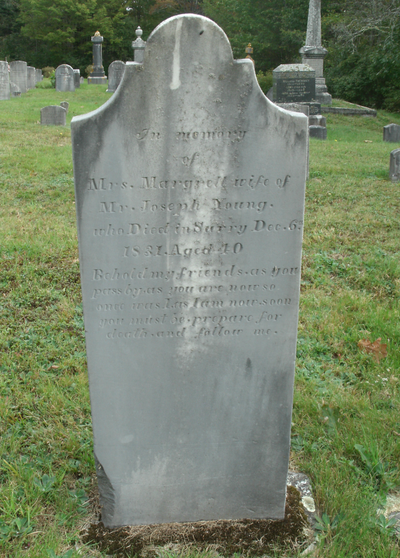

https://www.libraryireland.com/articles/ScotchIrishNewEnglandCongress1890/index.php http://hillfamilyweb.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Thomas-Means-Exhibit-Freeport-ME-Historical-Society.pdf https://www.maineulsterscots.com/ William Wormwood (1620-1690) My Wormwood ancestors who came to Maine in the 1630s landed in Kittery Point, then moved on to take part in the burgeoning fish trade on the newly-settled Star Island, one of the Isles of Shoals seven miles off the coast. The Maine frontier was rough, and unlike the Puritans who settled in Boston, people came there to fish, not to pray. Codfish was abundant off the Isles of Shoals, the average codfish weighing 150 pounds, and the fishermen supplied salted cod to early settlers from Massachusetts to Virginia. William Wormwood may have been a mate on fishing vessels but what we know for sure is that he and his wife, Catherine, lived in the fast lane for the times. In 1644 they sold their land in Kittery and moved to Star Island. Three years later, authorities expelled them from the island for “improper dealings” with sailors, presumably selling them too much liquor. The Wormwoods were cast off the Island with a man named William James, who moved in with the couple in Kittery. In 1647, Catherine was arrested and sent to the court in Boston to face charges of adultery. She was later released, though she and James apparently continued to carry on. Six months later the court ordered that William James and William Wormwood should “part household and for to build another house by year’s end.” That move did not keep Catherine and William James apart and in October 1650 the court again ordered that James “shall hence forward separate himself from Catherine Wormewood & must forthwith pay his Fourty shillings for his breach of the last Court order about his separation.” The historical record shows that William Wormwood became "a common swearer and a turbulent person" but he and Catherine eventually moved back to the Shoals, again shadowed by a court order that warned “if the Fishermen of the Iles of Sholes will entertaine Wormewood and his wife, they have liberty to sit downe ther provided that they shall not sell neither wine, beare nor Licker." The pair later returned to Kittery. The couple gave birth to several children, including my direct ancestor, another William Wormwood, in 1654, who became a carpenter and lumberjack. (See Massachusetts and Maine Families in the Ancestry of Walter Goodwin Davis, Vol. III) He also served as the constable of York in 1685 and 1686. Fatal Conflicts with Native Wabanakis This area, now part of York County, Maine, was a dangerous frontier where settlers lived inside palisaded garrisons to protect themselves from attacks from Wabanaki warriors backed by the French. William’s brother, John, and two other men were taken prisoners by Native Americans in 1676 and the regional British official, Richard Waldron (another of my ancestors), negotiated their release in Pemaquid by paying a ransom of twelve skins for each of the men. William Wormwood was not as fortunate. Fourteen years after his brother’s release, in October 1690, William was helping load timber onto a ship at nearby Cape Neddick when he was killed in an attack by a Wabanaki war party. Thomas Wormwood (1684-1751) . William’s son, Thomas, was six years old when his father died and he grew up to be a farmer and a fighter, living in the village of Larrabee, which was a fortified garrison. In the “History of Kennebunk Port” Bartholomew Gosnold, writes that in 1723, William took charge of Harding's Garrison while Mr. Harding was off on a hunting expedition. "The garrison housed about 30 women and children at the time. Thomas wasn't expecting an attack and took a boat to board some of the coasting ships that were in the river loading lumber. Thomas heard the alarm guns from Major's Garrison and returned and closed the gates when the Indians were within 20 yards of him. Sagamore Wahwa was irritated with his men for alarming the garrison just for the scalp of the white headed old man Mr. Bailey whose scalp they placed on a pole in view of the folks in the garrison. The Indians destroyed the remaining crops and killed the cattle who continued their raids through the fall.” Thomas’s son, William, was a soldier in Harding’s garrison when he and Ebenezer Lewis were loading a sloop under the command of Capt. John Felt in Gooch’s creek on April 25, 1724. The three men came under attack by Wabanaki fighters. The captain and Lewis were shot in the head but William Wormwood made it ashore, pursued by the warriors. He put his back against a stump to defend himself with the butt of his musket, but was shot several times and died. The bodies of the settlers were buried near Butler Rocks. (From: The history of Wells and Kennebunk, from the earliest settlement to the year 1820.) Joseph Wormwood (1718-1767) William Wormwood’s brother, Joseph, survived the violence that pervaded York county only to nearly lose his life when he was shipwrecked on Mount Desert Island. In 1746, 28-year-old Joseph was one of a group of 100 men pressed into service against the French near the end of King George’s War. The men from Wells and Arundel Maine crowded onto a ship heading to Nova Scotia that wrecked during a fierce snowstorm. All but a handful of men died. Wormwood and three comrades from Wells survived and made their way ashore onto Mount Desert Island, where they faced “fearful hardship and suffering.” (History of Wells and Kennebunkport) No houses existed on the island and the men shot fowl for survival as they fashioned a rough boat that they managed to sail south to Townsend (Boothbay) to find help. (From: The history of Wells and Kennebunk, from the earliest settlement to the year 1820.) Joseph returned to Wells where he married Sarah Evans in 1748. Their son Joseph, was born seven years later, in 1755. Joseph Wormwood, Jr. (1755-1838) Joseph Jr., married Mary Hall when he was 19-years-old and apparently the newlyweds left Wells shortly after the wedding heading to Township No. 6, Surry. Their daughter, Adnah, my 4th-great-grandmother, was born in Surry the next year, 1785. Joseph and Mary resided in Surry until their deaths in 1838. According to their gravestone markers, they changed their last name to Wood. Adnah Wormwood Ray died in 1853. Samuel Young was an early settler of Surry, Maine, arriving by 1778. His name was common, making it is difficult to determine who Samuel Young’s parents were, though the Young family dates back to the 17th century in the greater York, Maine area. A local historian who wrote the bi-centennial history of the town says the Youngs came from Old Newbury, Massachusetts. One source notes that a Samuel Young was born in 1735 in Northern Ireland, then emigrated. If so, he may be a Scots-Irish immigrant (link). We do know that before Samuel Young moved north, he married Elizabeth (Sarah) Joy on May 10, 1761, in Biddeford, Maine, a fact that could tie him either to the Young family in neighboring York or to a migrant from Old Newbury. According to Osmond Bonsey in his history of Surry, “the young settlers were sons who could find no land near their parents; others were people always restless, who never stayed long in any one place or who preferred solitary existence…These settlers were familiar with the area as they had often been to the east on fishing or trading expeditions.” By the 1780s, Bonsey writes, there were a number of settlers from "Old" Newbury, Massachusetts, including the Clarks, Treworgys and Youngs who settled on Newbury Neck in Surry. The historical record shows that these Massachusetts settlers were mobile, and many stopped in places like York or Saco, Maine, for a couple of years before trying their chances further north in Surry. Although an exact arrival date is impossible to fix, Young certainly arrived in Surry by the time of the American Revolution. Samuel Young's Revolutionary War Service He was mustered into militia service in July 1779, one of the hundreds of poorly trained farmers and mariners sent in at the tail end of the failed Penobscot Expedition. The 48-year-old farmer served for 17 days in Colonel Ebenezer Buck’s company of volunteers, which was part of Col. Josiah Brewer’s regiment and Col. Lovell’s brigade. Samuel Young appears as a resident of Surry in the 1790 census in a household with three males under age 16, three older than 16 and four females. He died three years later, in 1793, though his grave site remains unknown. A 19th-century biographical sketch confirms much of this. It reports that Samuel Young came from Saco, Maine, and “settled on (Newbury) Neck, close to the shore. He took up a tract of wild land, which by means of incessant toil he converted into a good farm. Like his pioneer neighbors he built a log house and there dwelt for rest of his life, rearing his family and reaching good old age.” Elizabeth Sarah Joy Young (1737-82) Another question that cannot be satisfactorily answered is the heritage of Samuel Young’s wife, Elizabeth Joy. The couple was married in Biddeford, Maine in 1761, and many amateur genealogists say she was born in 1737, a daughter of Benjamin Joy and Elizabeth Hovey. That would make her a sister of Benjamin Joy II, who is celebrated as a founder of Ellsworth, Maine, which borders Surry. Benjamin Joy appears in the early records of Township No. 6 and it would make sense that his sister and brother-in-law, Elizabeth and Samuel Young, followed him to the area. Joseph Cohoes Young (1778-1863) Samuel Young’s son, Joseph Cohoes Young, my 4th great-grandfather, was born in 1778, in Surry. His biographer writes that “Joseph Young was born in the old log cabin on the homestead which his father wrested from the wilderness. During his earlier years he was employed in coasting. Subsequently he turned his attention to farming, in which he was successfully engaged until his death at the venerable age of four score and four years. A son of sterling integrity, he became prominent in town affairs and wielded an influence for good in the community. To him and his wife, whose maiden name was Margaret Edmunds, eight children were born.” Margaret Edmunds Young (1791-1831)

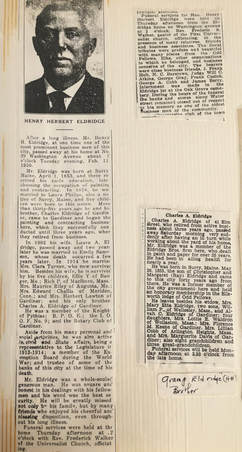

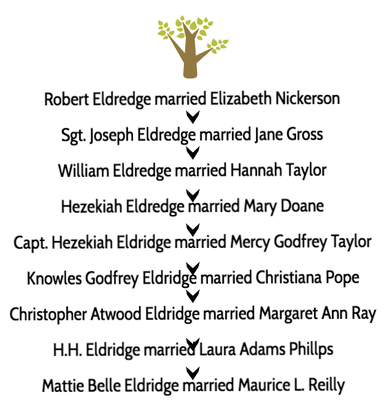

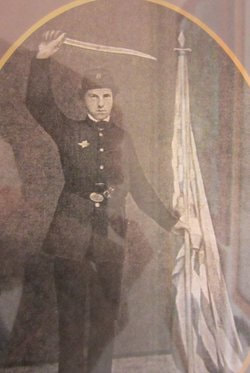

Margaret Edmunds’ parentage is much hazier. Death records say she was born in either Gouldsboro or Sullivan, Maine, but no one with this surname appears in the 1790 census. Other clues about any Edmunds living east of the Penobscot include the 1791 naturalization record of John Edmunds, an Irish immigrant who swore he had lived in the U.S. for at least two years and maintained a “good moral character.” John Edmunds was in Machias when he was naturalized and the same town recorded a marriage of John Edmunds and Jane M. Dole three years later, on February 16, 1794. A late 19th-century history of the Narragaugus Valley, which includes the area from Steuben to Machias, notes “the first school was taught by one John Edmunds, an Irishman, in the house of Mr. Isaac Patten, that stood near the Creek.” Margaret Edmunds was born in 1791 so whether she is the daughter of John and Jane remains a mystery. The marriage of Joseph C. Young and Margaret gave birth to Armelia Young, who married a sea captained name Henry Jarvis Ray. In 1852, Armelia and Henry Jarvis Ray’s daughter married Christopher Atwood Eldridge, whose father had moved the family to Surry a decade earlier. By 1862, both Christopher and Margaret were dead and their two young sons, my great-grandfather and great grand-uncle, went to live with their grandfather, Hezekiah Eldridge. (Read the full story of Robert Ray’s Scots-Irish parentage here.) at One of my great-grandfathers was Henry Herbert Eldridge, a descendant of a family that first settled in Cape Cod in 1635. H.H., as he was known, was born in Prospect, Maine, and my mother, who has a clear memory of him, said that he was known as a "whole-hearted, generous man," characteristics that, with luck, may still linger in our DNA. H.H. was born in 1853, the son of Christopher A. Eldridge and Margaret Ann Ray. His mother died when he was seven years old in April 1860, after a long illness. Two years and two months later his father, Christopher died at sea. Henry and his younger brother Charles were taken in by his grandfather, who operated a carding mill nearby. The boys’ grandfather, Knowles Godfrey Eldridge and his wife, the former Christiana Pope, raised his two grandsons at their home near the shipyard in Surry. In the 1870 census, 16-year-old Henry and his 14-year-old brother were listed as mariners. Knowles Godfrey, who was 73 that year and still worked at his carding mill. Twenty years earlier, in 1850, the census listed him as a clothier and in 1840 as in manufacture. When he was 25, in 1878, H.H. married Laura Adams Phillips, a descendant of another family that had settled Orrington around the same time Knowles Godfrey’s father settled there in the 1790s. Two years later, H.H. appears to have followed his grandfather into the manufacture of cloth. The 1880 census lists him as a woolcarder and his name appears on an 1881 map of Surry that shows “H.H. Eldridge Carding Mill.” Between 1879 and 1890, H.H. and Laura had five children, including twin girls, my grandmother, Mattie Belle, and her sister, Minnie. During this period, H.H. and his brother went into the painting business that had been started by another of Knowles Godfrey’s sons. By 1895, the Eldridges won the contract to paint Togus Veterans Home outside Augusta and the family moved to nearby Gardiner. For the next thirty years they ran the Eldridge Brothers Company with an office first at 9 Bridge Street then at 360 Water Avenue. After moving to Gardiner, fate struck the Eldridge family when H.H.’s wife Laura died in 1902. He married again, to Emily Sampson, in 1903, but she died of breast cancer seven years later. H.H. married again and his third wife, Clara, whom he married in 1914, was the only real grandmother my mother ever knew. Clara is pictured below in 1919 with my mother, age 2, and her two older sisters, Marjorie and Betty. Henry Herbert’s obituary in 1930 described his contributions to local Gardiner society. The Eldridges in Cape Cod In the 1960s, my mother and her sisters began to piece together the family tree, documenting that Knowles Godfrey Eldridge was born in Chatham, Massachusetts in 1797, just when his father, Captain Hezekiah Eldridge was settling in the newly-established town of Orrington, Maine. Knowles Godfrey’s mother was Mercy Godfrey, the daughter of another prominent Cape Cod family, and she passed her maiden name down to her son. Captain Hezekiah’s father was also named Hezekiah and there is little trace of him in the records other than a note that he had to tear down his house and barn, valued at 17 pounds, to stop the spread of smallpox in Chatham in 1765-6. Hezekiah, Sr. had married Mary Doane, a daughter in the well-established family that descended from Deacon John Doane of Plymouth. Hezekiah was the son of William Eldredge (1702-1753) and the grandson of Sgt. Joseph Elredge (1662-1735), who himself was the son of Robert and Elizabeth Nickerson, some of the original settlers of Chatham along with four Eldredge brothers.: Nicholas, Robert, Samuel and Joseph. Robert Eldredge first came to Plymouth in the Massachusetts Bay Colony as an indentured servant in 1635. He was listed to bear arms in 1643 in Plymouth then went to Yarmouth about 1645 where he married Elizabeth. He was constable in Yarmouth in 1657 and the family later moved and lived on a farm north of Oyster Pond in what is now West Chatham on part of the property deeded to Elizabeth by her father, William Nickerson, Chatham’s largest landowner. You can learn more about the early history of Chatham and the Nickerson family at the Nickerson Family website http://cnh.nickersonassoc.com/ ___________________________________________________ References: Genealogies : Eldred, Eldredge by Hawes, James W. (James William), 1844. A History of Chatham, Massachusetts: formerly the Constablewick or Village of Monomoit ; with maps and llustrations and numerous genealogical notes"Part 3 By William Christopher Smith ,1909 I’ve had great success researching my ancestors who arrived in New England 400 years ago but I keep running into stonewalls when I try to learn more about my Irish great-grandfather who came to New England about 150 years ago. Thomas Donnellan was a 20-year-old from Ireland when he sailed on the Ocean Wave from Ireland in 1865. I believe he married Margaret Cowan shortly thereafter and eventually fathered my grandmother, Mary Jane, in Manchester, Connecticut, in 1877. I am hedging here because the birth, marriage and death records for the family are nowhere to be found online. Thousands of Irish immigrants flooded America back in those years but the record of their family milestones are hard to unearth. I know Thomas died in 1891 because I’ve seen his grave marker at St. Bridget Cemetery in Manchester but it tells me little about the man. Manchester was a mill town back in the 19th-century, dominated the world-famous Cheney Silk Mill. Both my grandmother and her sister, Margaret, worked there but there is no trace of how their father was employed. There is more information about Mrs. Donnellan, born Margaret Cowan in Ireland in 1849. She came to America with her parents and six siblings before 1860. The photos below show Margaret Cowan, 1830-1884 (left), and her daughter Margaret Cowan Donnellan, 1849-1921. Margaret Cowan’s oldest brother, Francis, was listed as a weaver in the 1860 census but soon he was raising his sword high above his head in full uniform to pose for a photo before going off to fight with the Yankees in the Civil War, a fate common to many Irish immigrants. Frank Cowan served for three years in the Connecticut Fifth Infantry, marching from Harper’s Ferry, Virginia to the battlefields of Manassas and Gettysburg. He survived, presumably unscathed, and died in Manchester in 1886. I have few clues about how my great-grandparents met and married, where they worked or lived. I know they lost three infants early and two sons died young. Frank Donnellan got sick in Cuba during the Spanish-American War and died at age 23 in 1898. Here’s a photo he sent back home of him and his fellow soldiers in Cuba. Another son, Johnny, died young and only my grandmother and her sister, along with their mother, saw the dawn of the 20th century. Frustrated that there was hardly any trace of the parents of a man who died while serving his country, I decided to branch out to the Donnellan family in Springfield, Massachusetts who I understood were related to the Manchester clan. John and Anna Donnellan were brother and sister who lived in Springfield, Massachusetts all of their lives. They died there in the 1960s, both childless and unmarried. I know they stayed close to my grandmother Mary Jane Donnellan Peckenham because when I was born in 1955, they became my godparents and may be watching over me still. John was born in 1895, the son of Thomas Francis Donnellan. After graduating high school he joined the Army, where he joined the Chemical Warfare Service in World War One. After the war, he became an accountant, then spent 30 years as a postal clerk in Springfield. His sister, Anna, was born in 1899, and was a teacher, then a social worker in the department of public welfare. They had two other brothers, Edward, who became a prosecutor in Boulder, Colorado, and Thomas F. Jr. who started to join the priesthood then joined the welfare department as an interviewer in the 1930s. Their father, Thomas F. Sr., was born in Thompsonville, Connecticut, in 1865, the son of John and Bridget Donnellan, who worked as a laborer in the carpet mill in town. Before John and Bridget moved to Thompsonville,in 1860, they had been living in East Hartford, Connecticut, just down the road from Manchester. By 1870, John had moved his wife and three sons to Springfield, where the census takers noted that the 38-year-old had no occupation. His ten-year-old son Matthew worked in a “picture store,” while the younger ones were at school. John died by 1885 and his sons worked a series of jobs.

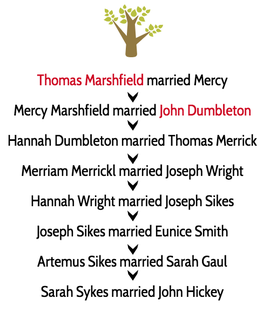

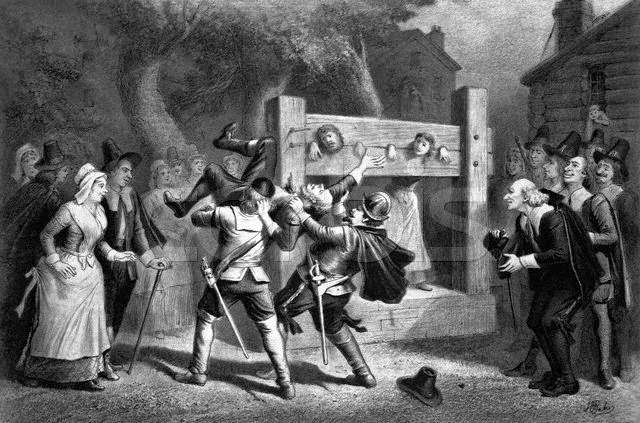

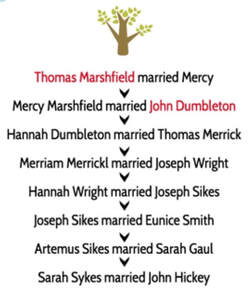

In 1893 Thomas F. Sr. went into the grocery and meat business with his brother Matthew, parting ways in 1899. By then, Thomas had married Bridget Teresa Burke and started a family. Thomas worked for the next ten or fifteen years as a bartender, starting at the Russell Hotel in 1902. In 1930, at the age of 65, he lived in a house valued at $9,000 and his occupation was listed as vulcanizer in a tire factory. His wife died that year. Thomas F. Sr., would have been cousins to my grandmother, Mary Jane, but despite hours of combing through online genealogy records, I cannot prove how they were related, or even better, what part of Ireland they called home. Neither his daughter, Anna, or his son, John, or their two brothers, ever had children and there are no cousins or aunts for me to contact to pick their brains. I remember the Donnellans because they were family and I knew them when they were alive. History has been less kind to the family, and after a century, their time on this earth is fading from memory. It was a woman baselessly accused of being a witch who first caught my eye. I was tracing the Puritan ancestors of my great-great grandmother Sarah Sikes when I read about Mercy Marshfield. Mercy lived in Springfield, Massachusetts in the 1640s and 50s and her legal fight to clear her name marked her as a strong woman. At the time of the trial against her accuser in 1649, Marshfield was a 45-year-old widow with three adult children and a son-in-law. The witchcraft accusation against her came from Mary Parsons, a Welsh immigrant woman in an unhappy marriage. The court of Thomas Pynchon, a gentleman who first settled Springfield, heard testimony about how Mary Parsons had slandered Marshfield, charging that she was known to be a witch when living in Windsor, Connecticut and that the devil had surely followed her to Springfield. Springfield residents, like faithful Puritans throughout New England, believed that witches displayed their powers in obvious ways. No one stepped forward to accuse Marshfield of any acts of witchcraft and Pynchon found Parson guilty of slander, then offered her a choice of punishments: either lashes or the payment of three pounds or 20 bushels of corn. Mary Parsons chose to pay the fine. It was not the last that Pynchon’s court heard of Parsons, who three years later accused her husband of witchcraft then was accused of witchcraft herself. Several neighbors testified against the Parsons, citing strange lights that jumped from clothing and a cow whose milk inexplicably dried up. Mercy Marshfield testifed that Hugh Parsons had cursed her and shortly after her daughter suffered from fits. Mary Parsonss was found innocent of witchcraft but confessed to having killed a child. She was sentenced to death for murder but died before the order could be carried out. Hugh was found guilty of witchcraft, then released after appeal. Mercy Marshfield in Windsor My ancestor, Mercy Marshfield, survived this drama but the stories led me to trace her roots in Windsor. There, it turned out, the entire Marshfield family had been abandoned by her husband and left to face the humiliation of the court seizing all of their property to pay off his sizeable debts. (Read more about Thomas Marshfield’s failed effort to enter the transatlantic shipping trade.) When the Marshfield family left Windsor, the settlement was at least ten-years-old. The Marshfields were among the original settlers who walked from Dorchester, Massachusetts in 1636 to settle on the Connecticut River. Hardships and deprivations, along with grueling months of farming, clearing land and trying to survive with few manufactured goods, took their toll. Mercy had only been in the colony for a year, having sailed from England to reunite with her husband in 1635. The fact that the Marshfields, without Thomas, managed to migrate to Springfield and start over, is a testament to their tenacity. Mercy’s son Samuel Marshfield and her son-in-law, John Dumbleton, became propertied members of Springfield society, serving as selectmen more than a dozen years each.

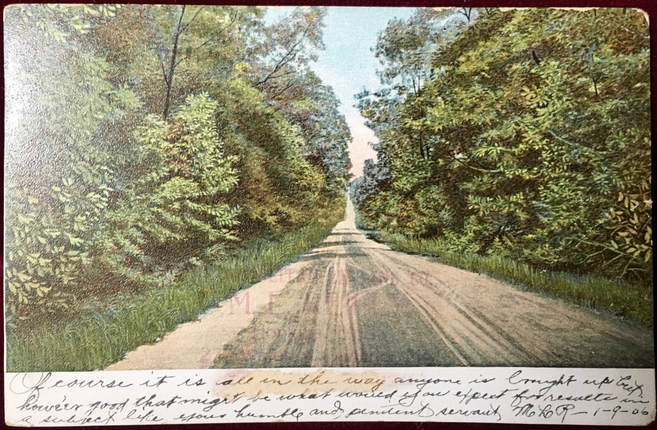

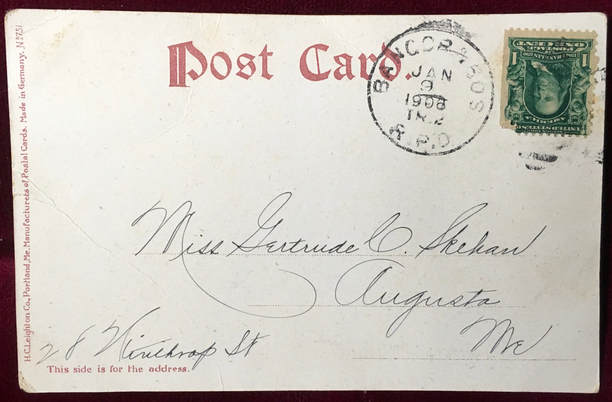

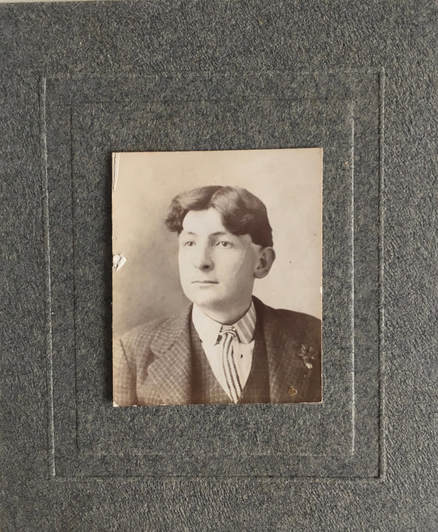

The postcard has been a prized possession of my mother for decades, its date revealing that it is more than a hundred years old. The country lane depicted on the card entices, pulling you in to the lush foliage that lines the way. Along the bottom margin, my grandfather’s elaborate handwriting reveals his skill. The photo on the card reminds me of Vigue Road in North Whitefield, Maine, where my grandfather Maurice Reilly lived as a young man. You can see his name in the faded red letters stamped onto the front of the card. The other letters are inscrutable though the handwritten note clearly expresses Maurice's belief in self-betterment, which he strived for throughout his life. It reads: “Of course it is all in the way anyone is brought up, but howe’er good that might be what would you expect for results in a subject like your humble and penitent servant MLR 1-9-06“ Maurice wrote the note on the card and dated it January 9, 1906, when he was just 21 years old. The postmark reveals it was mailed from Bangor, around the time when Maurice was first hired as a mail clerk on the railroad run from Bangor to Boston. Interestingly, the card was mailed to Gertrude C. Skehan, a 25-year-old clerk in Augusta who would eventually marry Maurice’s older brother, Ambrose, in 1910. Skehan was also from Whitefield and a member of St. Denis’s Church, where the Reillys also worshipped. At age 22 she was listed as a teacher, and later records indicate she studied through the first year of high school.

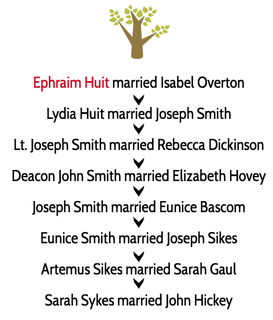

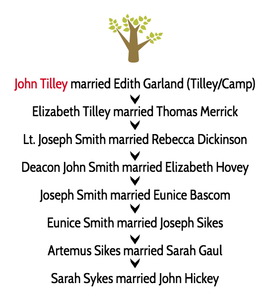

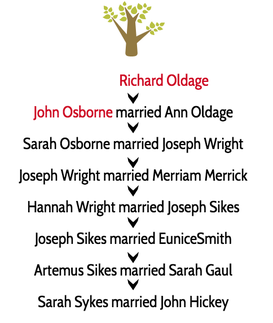

Of all the places my ancestors supposedly came from, no one in my family ever talked about Windsor, CT., recognized as the first settled town in the state. My mother traced her Maine ancestry lines back to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, largely to Cape Cod. My aunts had done some genealogy research back in the 1960s but they had traced back through the paternal lines only. Exploring the maternal lines of kinship in our family back more than ten generations I found hundreds of people who now populate my tree. Among them was Sarah Ann Sykes, a wizened little old lady in this photograph taken of her around the turn of the century. Sarah Sykes, it turned out, had been overlooked in the search for Yankee ancestors because, in 1843, she married John Hickey, an Irish Catholic immigrant, and dropped her Protestant faith to assume that of her husband. Her line, traced back from Bristol, Maine to the Pioneer Valley of Massachusetts and to Windsor, Connecticut, revealed dozens of 17th-century ancestors. Their stories revealed a constant migration that took them from Dorchestor, Massachusetts to Windsor, Connecticut then onto Springfield, Northhampton, Belchertown and beyond, fulfilling God’s command to “Go forth and multiply.” Our Ancestors in Windsor

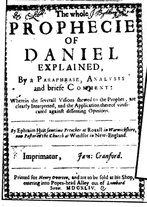

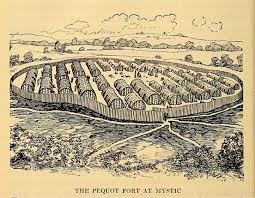

John Dumbleton married into the Marshfield family, but only after Thomas had disappeared. Dumbleton came to the Connecticut colony as an indentured servant to William Whiting of Hartford, one of the richest and most powerful men in the area, in 1638. For much of his seven-year indenture, Dumbleton worked a piece of Whiting’s land in Windsor that he later testified about: “There was little improvement on the land when I came upon it, but I plowed and brake up considerable quantity of it." When his indenture ended in 1645, Dumbleton leased the land for farming. Around 1649, Dumbleton migrated to Springfield along with the remaining members of the Marshfield family, a group that included daughter Mercy whom he married either just before or after their relocation to Springfield. Thomas Ford and Aaron Cooke Thomas Ford was a well-endowed 45-year-old when he came to the Massachusetts Bay Colony on the Mary and John ship in 1630, inspired by the Puritan teachings of Reverend White of , Dorchester, England. . His 14-year-old stepson, Aaron Cooke was with him, along with his second wife, Elizabeth Charde, and nine more children. One year after he arrived, Thomas became a freeman in Dorchester, Massachusetts, and Aaron Cooke followed in 1635. Like virtually all settlers in the Dorcestor plantation, the Fords were farmers and in 1636 they headed out with Reverend Warham's congregation to settle in Connecticut. In the new plantation, Cooke married his half-sister, Mary Ford. Her father, Thomas, filled many leadership roles, including on the jury of the General Court of Connecticut. Aaron became a captain in the local militia, in charge of training, and he was appointed commander-in-chief of a company formed to go against the Dutch who were still defending their claims on the Connecticut river. He also served several times on the jury of the General Court. Mary died in 1645 while giving birth to her fourth child. Her second son, Aaron, Jr., born in 1641, is my direct ancestor. Aaron, Sr., remarried three more times before his death. He worked some of his Thomas Ford’s 50 acres in Simsbury, Ct. (Massacoe), then received his own land grant in Northhampton, Massachusetts and moved there in 1660. Aaron Cooke, Jr. went to the same area and in May 1661 he married Sarah Westwood in Hadley, Ma. Ephraim Huit  He lived only six years in Windsor but Reverend Efraim Huit was a well-known Puritan in England, where he was stripped of his position because of views that were heretical to the Church of England. You can read more about Huit’s life in England in this excellent piece by genealogy blogger Janice Harshbarger here. Huit led a group of half a dozen families to join Reverend Warham in Windsor in 1638-9 and he became the congregation’s teacher. Remnants of some of his sermons have been preserved, including twenty-two based on the teachings of Timothy. His treatise on the Prophecies of Daniel was published shortly before his death. In Windsor, Huit undertook the task of building a new meeting house. He designed the structure and raised 200 pounds for its construction, borrowing most of the funds from wealthy Hartford resident George Wyllys. The loan was repaid with proceeds from a corn mill that had been donated to Huit and Warham by the congregation. The meeting house was completed in 1641 and Huit died three years later. Twelve years after his death.his daughter, Lydia, married a 19-year-old, Joseph Smith, who would be included in this story if he had lived in Windsor instead of nearby Hartford. John Tilley  John Tilley came to live in Windsor for economic opportunity, no doubt. Tilley was a sea captain and a fisherman who arrived in New England in 1624, before the Massachusetts Bay Colony had been founded and shortly after the Pilgrims landed in Plimouth. He was part of a group led by Robert Gorges to Cape Ann, where Tilley oversaw a failed effort to start a fishing venture. He followed Roger Conant to a new settlement that was renamed Salem in 1628. Sometime after the arrival of Governor Winthrop and the establishment of the Bay colony in 1630, Tilley removed to the new plantation of Dorchester. Tilley was captaining the ship Thunder to Bermuda in 1633 when he was sued for debt by his partners. It is recorded that just before he died in October 1636, Tilley was delivering letters from Governor Winthrop to Old Saybrook, sailing in the mouth of the Connecticut River. The Governor later described what happened: About the middle of this month, John Tilley, master of a bark coming down the Ct. River, went on shore in a canoe three miles above the fort (Saybrook) to kill fowl and having shot off his piece, many Indians arose out of the covert and took him and killed one other who was in the canoe. This Tilley was a very stout man and of great understanding. They cut off his hands and sent them before and after cut off his feet. He lived three days after his hands were cut off and themselves confessed that he was a stout man, because he cried not in his torture.” Tilley’s widow, Edith, lived in Windsor, where the couple had moved with the others who moved from Dorchester earlier that year. Their daughter, Elizabeth, who was four years old, grew up to marry Thomas Merrick, another Sikes ancestor. Richard Oldage  Most of my Windsor ancestors were well-known but Richard Oldage and John Osborn left little in the historical record. Richard Oldage was about 40 years old when he came to Windsor from England in 1639, part of the group led by Reverend Ephraim Huit whose non-conformists beliefs led him to seek the Puritan plantation. By 1640 Oldage owned land that stretched for three miles on the east side of the river, as well as land on the west side, the heart of the plantation. The only official record I found stated that in 1656 Oldage was appointed by the Connecticut General Court to be a “leather sealer,” an office that required him to give his stamp of approval on leather goods that he inspected, tested and certified. When Oldage died, his daughter Ann, my direct ancestor and his only child, inherited that land. By then, she had been married for about fifteen years to John Osborne. John Osborne Little can be found in the record about John Osborne, who was born in either England or Wales in 1621. His father’s name has not been verified, but in his will he signed his name John, Senior, indicating that he was not named after his father. John Osborne’s name is listed as a founder of Windsor, Connecticut, a status given to any male settler who arrived by 1641. John would have been 20 that year and it is unlikely that he would have been given any land grant at that age. He may have come to Windsor as a tradesman, but the historical record has not turned up any evidence of his occupation outside farming, which all settlers practiced by necessity. The historical record is contradictory about his wedding date. They agree that the marriage occurred on May 19 in Windsor, but it is recorded as 1643, ‘44 and ‘45. His wife, Ann Oldage, inherited her father’s extensive land holdings, about 1,000 acres, after his death in January 1659/60. John Osborne became a freeman of the church in 1669, a year after my direct ancestor, Sarah Osborne married Lt. Abel Wright and removed to Springfield, Massachusetts, leaving her Windsor family behind. Benedictus and Joanne Alvord  Benedictus Alvord is remembered as a founder of Windsor, having arrived their shortly after he sailed from England at age 11 with his brother and sister, Alexander and Joanne. Joanne is my direct ancestor but Benedictus’ role in history cannot be overlooked. He was a sergeant at age 18 in the 1637 war against the Pequots, when hundreds of natives, mostly women and children, were massacred when the soldiers set their homes on fire and sealed the exits. Benedictus Alvord returned to England the next year and married. His bride was a passenger on the ill-fated ship charted by Thomas Marshfield in 1640 and Alvord sued Marshfield for ten pounds. In Windsor, Benedictus prospered, serving as a juror, then as constable in 1666. He passed away April 23, 1683 in Windsor, Hartford, Connecticut.

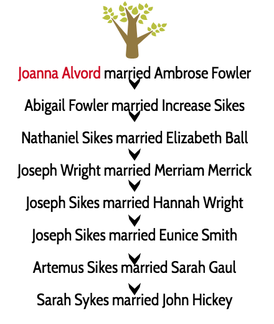

Joanna (Jane) Alvord, his sister, married Ambrose Fowler, who did not appear in Windsor until 1640, when he was 14. By age 19, he and Joanna were parents. The family stayed in Windsor at least another 18 years, then removed to Westfield, Massachusetts, where their eldest daughter married Increase Sikes, great-great-great-grandfather of Sarah Sykes. |

Names of My AncestorsPuritans & Servants Archives

February 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed